In late 18th century America, the most petty, brutal political battles were often duked out on newspaper pages. It was common practice for one to publish their political opinions under a pseudonym. John Dickinson penned his famous series of essays under the simple “A Farmer”, Thomas Paine often wrote as “Vox Populi”, and the writers of the Federalist Papers, originally serialized in newspapers, were published under the collective pseudonym “Publius”. One reason for this practice was that anonymity gave one’s writings a more “democratic” tone that allowed the reader to focus their attention on the arguments given and not on the person who voiced them. The pseudonyms provided as examples above all have an implication that the writer was speaking merely as a member of the general American public, and that therefore it didn’t matter who wrote it because the sentiment of the writing was already felt by many.

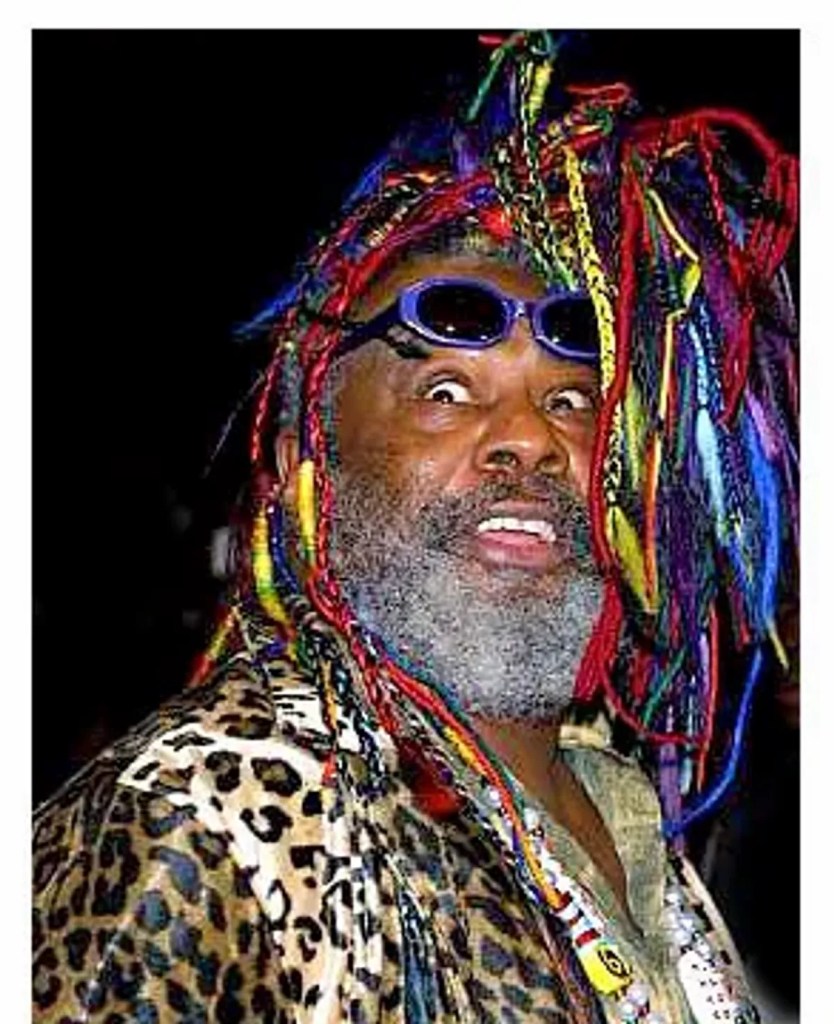

However, although the pseudonym on the face of it was a means to make your argument less personal, it ironically led to some of the most obviously personal quarrels being aired out publicly. Anonymity, at a time when duels were still openly, though rarely, fought, provided writers with the security to truly express how they feel, to speak frankly and often far more cruelly than they would ever dare to under their own name. However, sometimes the grievances expressed were so deeply felt, so personal, that the pseudonym did little to hide the identity of the writer. Robert R. Livingston, through just such a pseudonym, was once embroiled in a vicious public exchange that ultimately resulted in some of the meanest things ever publicly written about him (as well as some of the meanest things that he ever dared too publicly express).

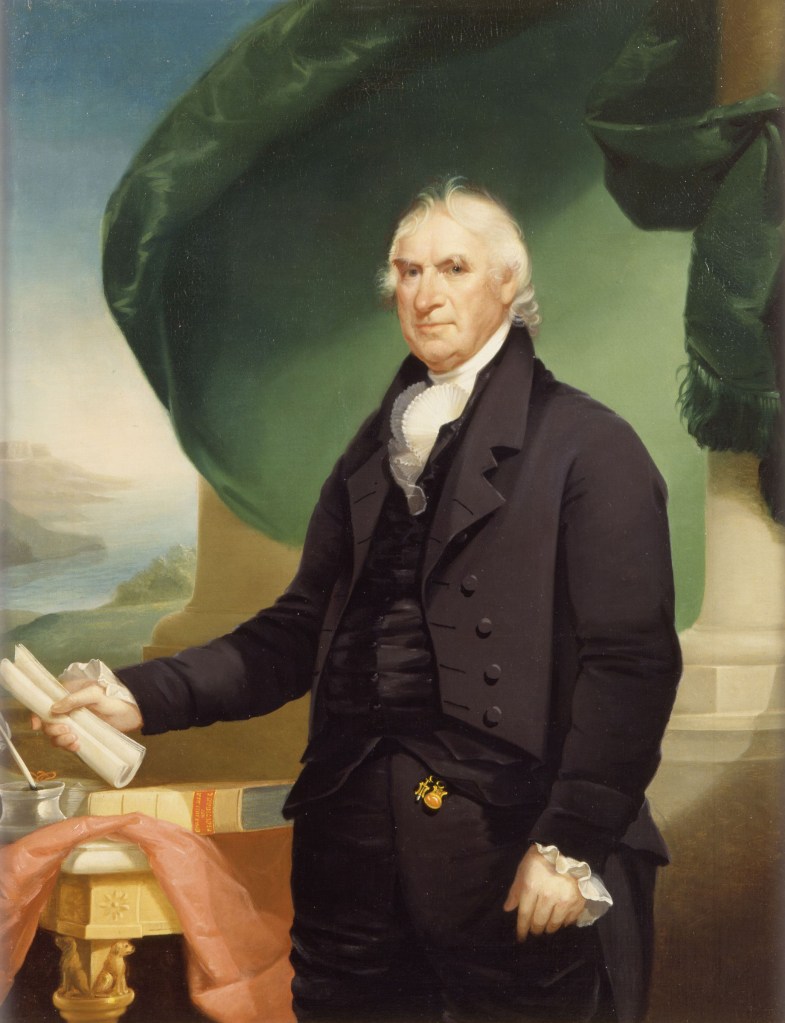

Livingston, during the gubernatorial race of 1792, was waging a particularly nasty press campaign against John Jay. Jay had once been his business partner, his political ally, and above all his close friend, but the relationship began to sour in 1789 when Jay joined Washington’s administration as Chief Justice while Livingston failed to acquire a cabinet position at all. By 1792, Livingston had politically converted from Federalism to Antifederalism and endorsed George Clinton against Jay as governor of New York.

An unfortunate benefit of anonymity is that it allows one to spread misinformation more freely, which Livingston did knowingly in his letters tarring Jay. Writing anonymously, Livingston pooh-poohed Jay’s role in negotiating the Treaty of Paris (which ended the revolutionary war)- “[l]t would be the grossest flattery to Mr. Jay to attribute the treaty with Britain to him alone, when we consider that the immortal Franklin, the philosophic and amiable Jefferson, and the learned Dr. Adams were his associates in this work…” Jefferson was not involved in any way with the treaty negotiations-he wasn’t even in Europe at the time– but he and Livingston had become political allies, so perhaps Livingston’s blatant lie was intended to provide the Antifederalists with some unearned clout. Livingston’s cover of anonymity slipped away further when he puffed up himself in the same letter: “[T]he points that particularly distinguish [the New York State Constitution] from that of other States in the Union… [are] indebted as I have heard to Chancellor Livingston…” This was only one of many polemics Livingston published against Jay during this gubernatorial race, many going beyond the pale in their criticisms, and it was only a matter of time before these writings received a Federalist response that attacked their author directly.

Enter Timothy Tickler. On March 31st, 1792, a letter was published in the New York Journal purportedly from “a friend of the M[ano]r of Livingston]n” addressed to the Chancellor. Within the letter, Tickler, whoever the pseudonym may have belonged to, didn’t bother to waste any time attacking Livingston’s political views and instead went straight at Livingston’s character. First, he claims that Livingston is the author of most of the anti-Jay writings in the newspapers (many of those he names directly, importantly, were likely not Livingston), but then goes on to say that Livingston’s character, or lack thereof, leads these essays to be useless to Clinton’s cause. Livingston’s narcissism, he argues, is palpable even in an anonymous text. “The friends of C[linto]n… seem to relish the praises you have lavished upon yourself almost as little as if they had been bestowed upon Jay. It was only but this morning that one of them… could not help regretting that ‘the C[hancello]r’s modesty should be so often obliged to violate itself.”

Timothy Tickler even takes some time to mock the Livingston family for being divided over petty disputes regarding land ownership and rights to use the Roeliff Jansen Kill for a grist mill, referring to the fight as “the important quarrel of the straw mill, which, like the siege of Troy has lasted these ten years…” He insults the family further: “[T]hough this [family] cannot be called an aristocracy (composed as it is of many of the worst and weakest men of the state) yet it is such a combination as every genuine republican will, in his heart, either despise or abhor…”

Excepted here are some of the worst attacks that Livingston is dealt by Tickler:

“[Many say] that you had some imagination but no judgement; that of course you are to be found always at the surface of things, never at the bottom; and, in general, that there are some coins that are current for more than they are worth.”

“The new government had many high offices and snug places to bestow. The C[hancello]r’s vanity would not permit his ambition to sleep. He tendered his services. The President knew how to appreciate merit, and passed him by.”

So, who was Timothy Tickler anyway? The letter betrays an extensive knowledge of Livingston’s career and character, employed brutally to cast doubt on the credibility of both. One often suggested theory alleges that it was Livingston’s own brother-in-law, John Armstrong Jr., at the time still a Federalist, and that Armstrong may have written it as a favor to friend Baron von Steuben, who took offense at being called a “pensioner” in one of Livingston’s anonymous letters. This theory is appealing, both for the familial drama, and because Armstrong has his own history of incendiary essays beginning with the coup-proposing Newburgh Letters. But ultimately, the identity of Timothy Tickler has not been proven in any conclusive way. Livingston, however, jumped to conclusions, and quickly made the bitter assumption that Tickler was none other than Jay himself.

The Chancellor, having been wounded by what he believed were scathing character attacks from a former friend, went after Jay on an equally (if not worse) base level of personal criticism. On April 4th, within a week of the first letter’s publication, Livingston published his retort under the classical pseudonym Aristides, addressing the letter to “the Honorable Timothy Tickler, Chief Justice of the U.S.” The letter that follows is practically bleeding with personal hurt and resentment. Livingston, as Aristides, briefly defended his own career and talents only to turn to attacking Jay’s: “[S]ir, you of all men should have been cautious of provoking an investigation into the extent of your talents. You, who in every walk of science and polite literature, are far, very far, behind your compeers… Come forth, sir, and shew a single act of yours, even in politics, which has long been your only study, that betrays the smallest mark of genius.” The Federalists, he wrote, when they nominated him viewed Jay “not as a good in yourself, but as the lesser of two evils… to be swallowed… not as a wholesome and palatable food, but as the pill that nauseated as it cleanses the stomach…”

In a more explicitly personal argument, as the former friend of Jay’s, Livingston claims that Jay has abandoned all his friendships. “I would begin… by telling you what your friends say of you. But where, sir, shall I find those that are entitled to that endearing appellation? Among the companions of your youth? These you have sacrificed to a mere jealousy of their superior abilities, to an overweening ambition, which made you dread them as rivals… Shall I come still nearer home, and enquire for your friends among those with whom you are connected by marriage [Jay, importantly, had married a Livingston], or the ties of blood? From the hearts of these, too… your deadly and implacable resentments have forever expelled you: nay, so unfortunate is your situation, that your cold heart graduated like a thermometer finds the freezing point nearest the bulb…” In short, Livingston’s central point was that the more you get to know Jay, the more you found to dislike.

The letter, while framed playfully as a friendly corrective piece, certainly pulled no punches in mercilessly attacking someone who was once Livingston’s closest friend. After the publication of this piece, Jay only put out a brief statement, dated on the same day as the Aristides letter and signed with his own name, that he had nothing to do with the anti-Clinton political papers. “Whoever they may be, they have not been actuated by my advice or my desire; and not being under my direction or control, I cannot be responsible for the pain their publications have given.” One can only imagine how Jay felt, firstly that his former close friend believed him capable of writing such a cruel polemic against him, and secondly that the same close friend would stoop to write an equally brutal piece in reply. In a letter to Washington in 1794, Jay writes briefly (and perhaps with a note of sadness) of Livingston, but ultimately excises the mention altogether: “With that Gentleman, I had been in the Habits of Intimacy and Friendship- about a Year ago he suddenly, and without Explanation reversed his conduct he was probably under the influence of Errors, which Time will now or hereafter correct.” Time didn’t ever correct this misapprehension; Jay and Livingston never resolved their differences.

At the very least, it can be seen through this exchange that the medium of pseudonymous newspaper essays gave writers a license to speak remarkably freely and cruelly, and the consequences of this anonymous speech, at a time when near everyone was reading these newspapers, were often major and unexpected. Livingston, in his initial anonymous letters, made the first steps in turning what should have been a campaign around political differences between the Federalist and Antifederalist camps into a petty personal rivalry. But Timothy Tickler made this turn complete by bringing the Chancellor’s character explicitly under fire in a gubernatorial race where Livingston wasn’t even a candidate. Timothy Tickler, whoever he was, was able through a short anonymous letter to sow vitriolic rhetorical chaos in late 18th century New York. The ultimate victim of his polemic was not Robert Livingston but Jay and Livingston alike, bringing about the final loss of any hope of reconciliation between the two former allies and friends.

Links and sources for further exploration:

George Dangerfield pgs. 256-260

https://csac.history.wisc.edu/2022/07/22/pseudonyms-and-the-debate-over-the-constitution/

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-05-02-0191#JNJY-01-05-02-0191-fn-0006

Leave a comment