Tours at Clermont are typically framed around the last generation to live in the house. This means that we frequently discuss the last two girls to grow up here – Honoria Alice Livingston and Janet Cornelia Livingston. However, these two share a half-sister – Katharine – who was a product of their father, John Henry’s first marriage. Although Katharine was much older than Honoria and Janet (she was in fact quite close in age to their mother, Alice…. but that’s another story), she serves as a starting point for the changing way of life for women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born in 1873, Katharine Livingston spent a portion of her childhood living with her maternal aunts in New York City. Her mother had died from complications of childbirth and the Victorian social mores of the time dictated that John Henry Livingston could not properly raise a young girl as a single father. It was not until 1880, when he remarried, that Katharine came back to Clermont to live with her father and his new wife, Emily Evans. The family lived happily together until Evans’ death in 1894. In their grief, Katharine and her father embarked on a World Tour that included travels to the far east and Egypt as well as Katharine being presented to Queen Victoria.

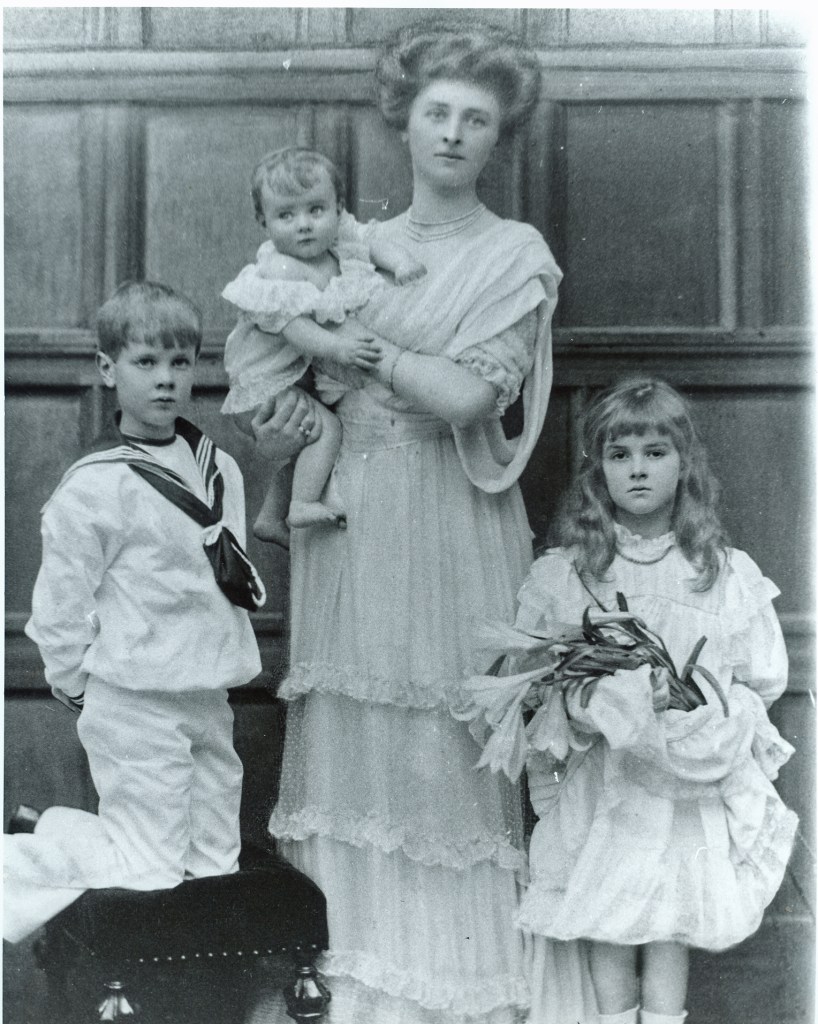

By 1900, Katharine had married Lawrence Timpson at Clermont, with John Henry giving her away, and the couple soon moved to England to start a family. They would go on to have 5 children, 12 grandchildren, 18 great-grandchildren, and 30 great-great grandchildren (as of 2019). Katharine would be the only one of John Henry’s daughters to have descendants of her own. This also made her the one to follow what we tend to think of as the “proper” trajectory for young ladies at the time. She married a wealthy man and raised children in a home where she was the mistress of the house – the life pictured for a Victorian Lady. However, this expectation begins to shift not that long after and we can see it reflected in Katharine’s younger half-sisters.

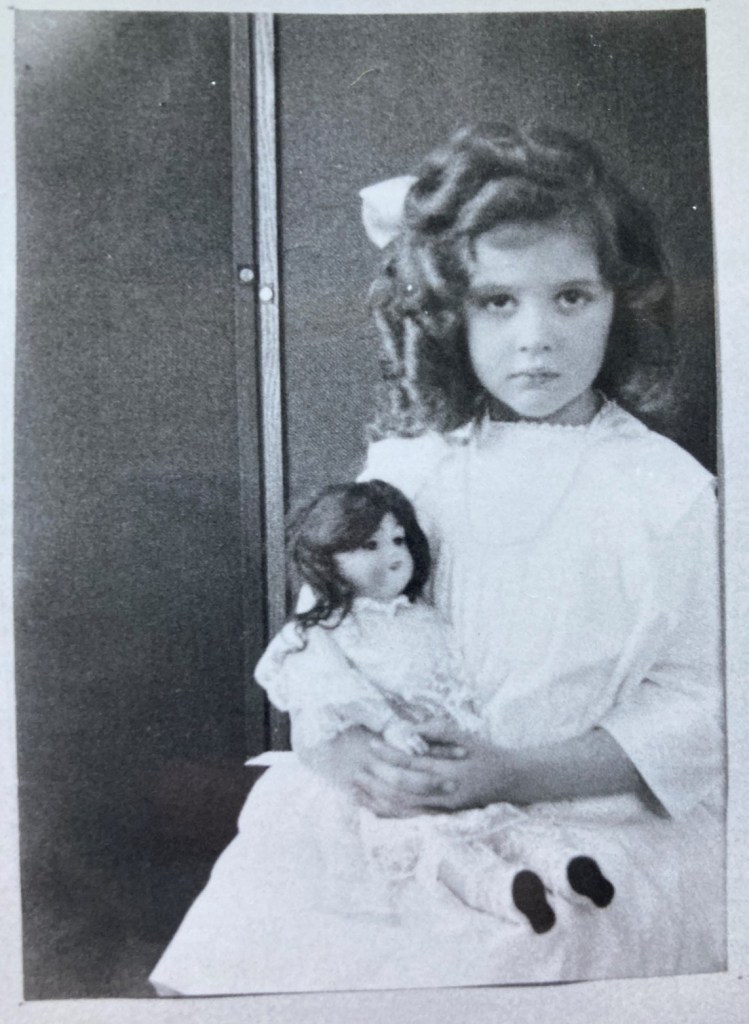

Next up is Honoria Alice Livingston, born in 1909. When you picture a young lady from Old Money in the early 1900s, chances are you picture someone like Honoria. When her mother, Alice, wrote down stories about her daughters, Honoria always seemed to favor activities generally regarded as “girly”. As spring approached, Honoria (or “Noya” as she was nicknamed) expressed excitement for the coming bloom of wildflowers and enjoyed slowly riding along in the pony-cart and stopping frequently to collect them. On another occasion, Honoria was singing in another room apparently so beautifully that Janet told her to wind the music box up again. Honoria answered “sedately” and said there was nothing to wind. She is typically described with a radiant face or excitement as she shares her love for her family. When the family lives in Italy in the 1920s, it is assumed that Honoria takes great interest in the more “domestic” pursuits like embroidery and music while Janet is taking fencing lessons.

In 1931, Honoria married a man by the name of Reginald “Rex” McVitty. With his Irish ancestry and her Old New York Money and name, they seemed like an attempt at a Transatlantic marriage – combining American wealth with European nobility. At the end of the day, they were both far from destitute but also not insanely rich. But they loved each other. One rumored story of their meeting involves them locking eyes across a room of people at a party, an easy feat as they were both 6ft tall or more. Honoria and Rex settled into life at Sylvan Cottage on the Clermont property while also maintaining residences in New York City and Sarasota, Florida. Honoria once again seemed to be ticking the boxes of a “typical” young lady of society in the early 20th Century. However, while she did marry like her older half-sister, she and Rex never had any children. There are many possible reasons for this including medical complications and just plain not wanting children. Regardless of the reason, it didn’t seem as though Honoria faced any judgement for remaining childless and not continuing the Livingston line. This represents both a privilege of her status as a woman with money and options and also a changing view in what is the “right” path for women of the time.

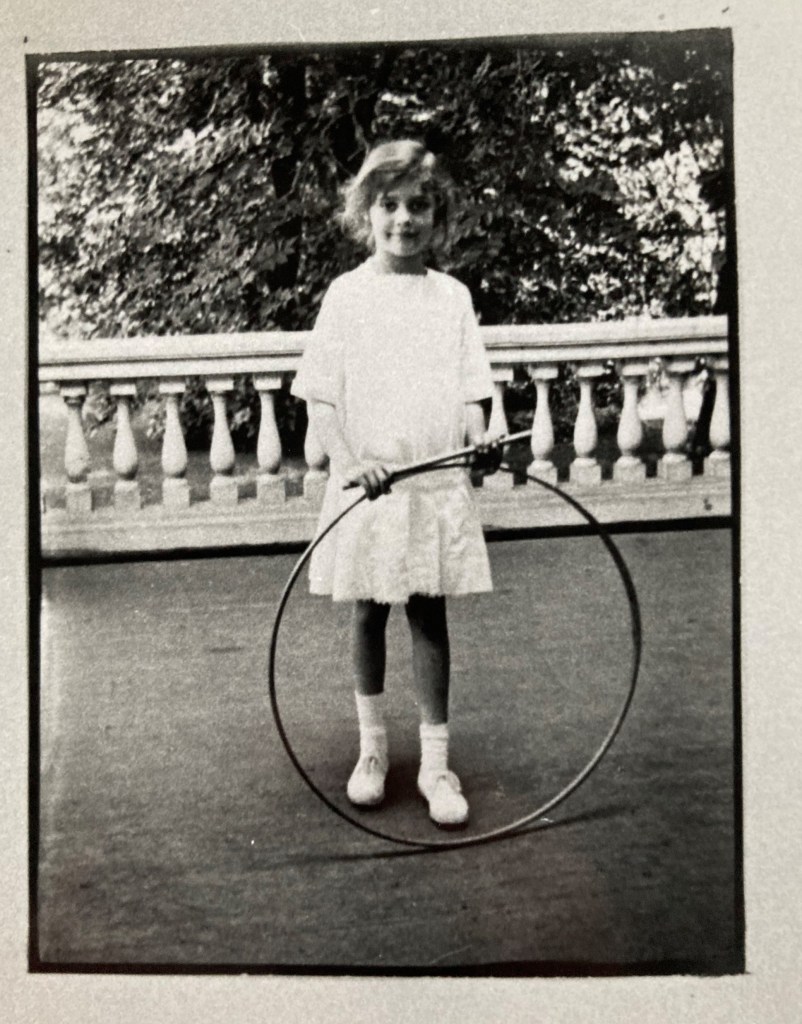

Then there’s Janet. Janet Cornelia Livingston, born in 1910, tends to be viewed as an outlier in both her family and in her role as a woman in the early 20th Century. When Alice wrote about Janet, she was a clear contrast to Honoria’s “ladylike” ways. She seemed to have been a very sarcastic child, with one instance involving Alice telling her to remember her good manners and Janet saying that she will “put that on [my] list”. She also wished she could have two mothers so that she could have Alice and Honoria could have the other mother. By today’s standards, Janet would be looked at as a “tomboy”. But how unusual was she for her time?

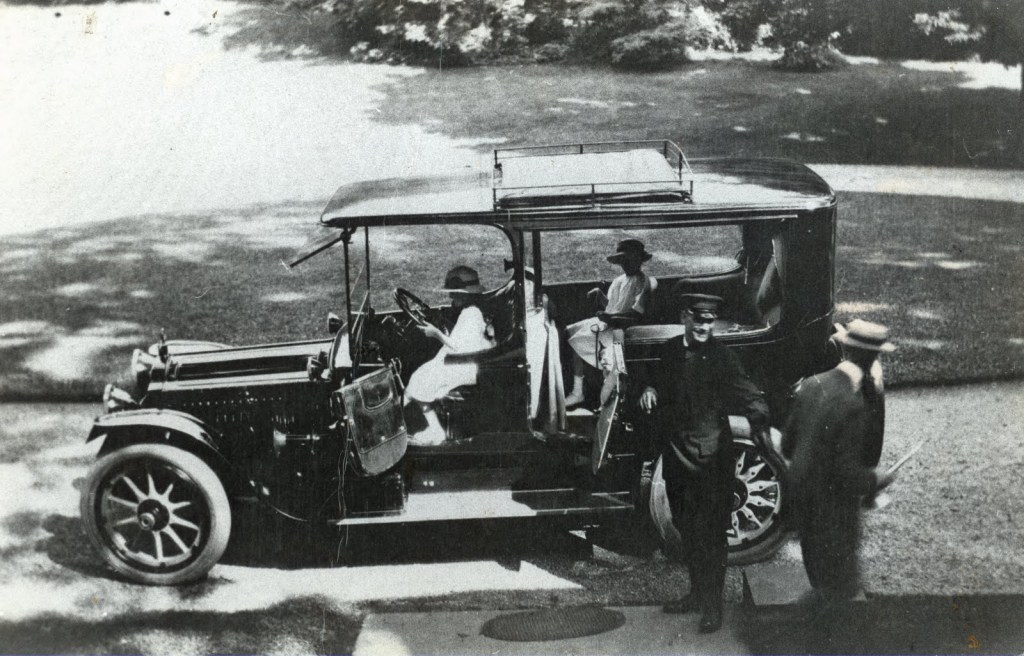

First, we have her love of cars. It’s common to think that etiquette rules of the 20th Century would instruct women to enjoy calm and leisurely activities like strolls and being chauffeured around. I know that I generally assumed that love of driving was perceived as a more masculine activity. And yet…Emily Post, Miss Manners herself, was a great lover of cars and very much believed that driving was a perfectly acceptable activity for women. In fact, before she became known for her etiquette guides, Post was a bit of an automotive journalist. She took a cross-country road trip with her son and while he drove and she was the passenger, she wrote about how a woman should comport themselves while driving. In an etiquette guide she mentioned that a “woman should never take up more than her fair share of the road” and encouraged women to learn to drive in order to maintain independence.

The other anecdote about Janet that always stands out as “unladylike” is when she thanked Alice profusely for her first toy pistol so that she didn’t have to just jump out and yell “Bang!” The stereotypical idea of games for young ladies in the early 1900s tends to be dolls and dress-up and quiet activities, not cops and robbers. And yet, was it so strange for Janet to want a toy pistol? We know she went on to become a skilled fencer in her teens so weaponry was not out of the realm of possibility. And remember, we are in a time when someone like Annie Oakley was so renowned for her sharpshooting skills that she was invited to perform for Queen Victoria in the late 1800s. This indicates that firearms/shooting as a hobby would not have been forbidden to girls. Through research I also found advertisements for pistols specifically made for women and children to enable them to protect themselves if “the man of the house” was away. I know that I always assumed Janet playing with a pistol would’ve been unheard of for a young lady but instead it seems that the idea of what was appropriate for girls was changing in the 20th Century.

Janet ultimately went on to study at business school and to begin working at New York Chemical Bank. She received her pilot’s license, became an avid equestrian and continued her love of motor cars. We also know that she never married and never had any children, choosing instead to maintain an apartment in New York City and to live in Clermont Cottage with her mother when upstate. Janet remaining unmarried could have been for several reasons: it’s possible she never met a suitor she liked, it’s possible she wasn’t interested in marrying a man, or it’s possible she wasn’t inclined towards marriage or romance at all. Whatever the reason, living out her life as an unmarried woman makes Janet Livingston seem unique for her time especially in a well-regarded family like the Livingstons.

When I planned to write this blog, the idea was going to be: isn’t Janet an anomaly for the time? Isn’t she a contrast to what we perceive as the “ladylike” woman if the early 1900s?

And yet it turned out that she wasn’t less “ladylike” than her sisters, just inspired by changing ideals of femininity. When looking at Katharine, Honoria, and Janet, we can see a clear shift in expectations for women from the Victorian Era into the 20th Century. The important thing is less that Honoria marries but doesn’t have children and Janet never marries at all than it is that they have that option. Prior to the 20th Century, women typically had their lives laid out for them. Katharine happens to follow that path, maybe because she wants to and maybe because she is expected to. But her younger sisters are able to make more choices as they grow up in a new time.

The status of the Livingston name is certainly a factor in the freedom of these women but the progression of women’s rights also plays a part in their life paths. And, as the last generation to grow up at Clermont, Katharine, Honoria, and Janet are the clear conclusion to this series on The Lives of Livingston Ladies.

Leave a comment