Janet Livingston Montgomery, eldest daughter of Margaret Beekman Livingston and Robert the Judge, is a staple in our Legends by Candlelight tours here at Clermont. Most of that is due to her tragic love story with Richard Montgomery, a soldier in the American Revolution, but there is an element of Janet’s story that reads so melodramatically that we’ve done programs entitled “Janet Livingston: All My Boyfriends are Dead”.

So today we have enlisted Janet herself to tell her story. No, we didn’t conduct a séance (this time), instead we turned to Janet’s “Reminiscences” which she dictated to her niece, Coralee in 1819 or thereabouts. With no children of her own, Janet called upon her beloved youngest brother, Edward, and his daughter to make sure her memories were passed on

So, in her own (abridged) words, here is Janet Livingston Montgomery.

Having passed through many strange scenes in my life, my little journal of the past, should I have courage and life to finish it, for now I am in my seventy-sixth year, may one day when I am gone, interest you my dear Brother, and recall to memory her who always loved you with a love surpassing woman’s love. Nineteen years younger than myself, you know little of my youthful years…You will smile when you read the trifling tales, and yet as everybody cannot go back to their great grandfathers, I have a pride, an honest pride I hope it is in worth knowing they were of high worth and honest men.

From infancy I became a favourite with my father’s mother, unfortunately, as I was spoiled with indulgence…With this tender parent I lived until my twelfth year, when her sudden death changed my destiny. I was taken home to my parents.

Would you know more of your ancestors? I can detail more to you. My grandmother told me of her marriage and of a circumstance which moved my wonder. She was persuaded by some girls older than herself to go to a fortune teller. After the girls were satisfied, the old woman looked at her with some surprise and asked if she would not hear hers – she shrunk abashed – the woman persisted, and told her she would be wedded to a Dutch-Scotchman and if she chose she would [shew] his face to her in the glass – her flight was instantaneous – fear gave wings to her feet – yet however absurd the prediction was literally fulfilled and a Dutch-Scotchman was her husband. (This tale refers to Margaret Howarden, her paternal grandmother, who married Robert the Builder, descended from a Scottish-born, Dutch-raised father and Dutch mother.)

My mother’s mother, as I have before said, was daughter to the first Livingston that came to this country, the uncle to the first Lord of the Livingston Manor…This lady died very young, and I was called after her, which might be another reason for my grandfather’s partiality for me. After her death he married a fine lady of ancient date, who had lived with all the great people then known. She had been a beauty, and failed not every day to tell me of it, lest I should forget what then was not. She was to me the bitterest pill I ever had to swallow…

She had all the politeness of a woman of fashion and all the cunning and intrigue that her weak intellect would allow. She neither loved my mother nor any of our family, except one of my younger sisters, who was very beautiful and called Gertrude after her. On me she was a jealous spy, and if my grandfather had not been a man of good sense and of the best heart, I should have lost his favor.

As I grew older, I also began to think of some new arrangements. I had hitherto seen my young acquaintances in a corner behind the chairs of my ancients. I had often wistfully cast my eyes on a small front room; but that, alas, was occupied by a little hump-back wasp of a steward and agent, who had it in possession for fifty years. I had all the servants in my interest, and by their means removed some large guns, which hung over the door, and two large pictures of Indian pheasants cracked in a thousand pieces. I then had the room washed, and my friends were introduced. The agent still kept his station, sitting on a chair, with three large books to raise him to the table on which he wrote…

I took furniture from my father’s house, and I found this room so comfortable that it became my sanctum sanctorum, and repaid me for all my troubles past…

I found a bunch of old keys, one of which unlocked a closet that certainly had not been opened for fifty or sixty years. It was filled with double bottles marked with my grandfather’s name. I took one down, thinking I had joyful news to impart to him. I told him of my discovery and poured him out a glass. There was a think oil upon it and it was perfectly white by age. Whether his mouth was out of taste, or whatever was the cause, he seemed not to like it. And told me I might do what I pleased with it. I was well convinced he was mistaken, ran off with my prize, and took good care not to tempt him by a second glass.

A history of a woman without mentioning her lovers would be a stoicism. My memory would fail in recollecting my [juvinel] beaus. I had one who wrote me letters ere I could read writing. He was heir to a great estate and this was a family project…I took such disgust to him that I would never hear of him afterwards. After some years he married and in a fox chase broke his neck. I mention this merely to tell you that there was a fatality attending most of those who offered themselves.

One young captain, a modest Scot, [shewed] much good will, informed me that he was going home for higher commission and then he hoped to find me disengaged. I made him no promise. He set sail and was lost at sea.

Two gentlemen, brothers to the person who wrote my grandfather’s will thought it would be a convenient thing to have rich wife – proposed for me – but they neither of them pleased me. I who had neither beauty or talents (although flattered) could not help wondering at these attentions.

I nearly fell in love with an officer who had only his great beauty and his regimentals to boast of – he had neither education nor talents. I saw these defects and yet in despite of all gave him a preference. I would have been his wife could my parents have consented.

One I will attempt to speak of, though even at this distant day it will be with a pang of sorrow. It was of a gentleman who was a lover and yet no lover…Together with the three ladies in our house I obtained leave to see a play. He was one of the party and took his seat beside me. His wit and politeness engaged my attention, and from that hour he declared himself devoted to me.

How it would have finished, I hardly know, but for a dreadful catastrophe. He was the idol of his companions – no party could be joyous without him; his wit, his humor, his powers of taking off anybody he please, kept the table in a roar. The folly of this kind of life, he had determined to lay by. He had commenced his reform and refused to join his friends for several weeks. Those friends could ill spare him, and laid a plot for his ruin. They met at a tavern and sent him several messages, all of which he refused. At length they went to his house in a body and forced him to accompany them. When once in the circle the jest and the wine went round, and all his resolutions were lost in the vortex of folly. They sat until day appeared when a ride was proposed, and inebriated as they were they set off. After a short ride one man fell from his horse and the rest got off to assist him, but my poor beau insisted that he was dead and ordered silence while he repeated the funeral service. This being done he again mounted and soon came to a bridge, where his horse stumbled. He fell and never spake again.

What was surprising, I was prepared for this dreadful event by a dream. I have told you that I have great faith in them, and should I ever live to go through this eventful life, I may reduce your doubts to certainty.

About this time a gentleman arrived who had served in the British Army from his fifteenth year…and here he concluded to settle, but with a determination never to marry and not to draw sword again. It was singular that he should have broken both these promises ere he had been three years in the country. Ten years back I had once seen him. He came on shore at our country seat with all the officers of his company, and politeness led him to make me a visit. What need I say more? He became attached to me, and with the consent of my parents I became his wife.

I married in the year 1773 surrounded by my parents, my grandparents and a large company of brothers and sisters with the consent of all. No one was connected under happier circumstances and the only thing that gave me a secret pang was my father giving me away.

The foundation of a house was laid and a happy home seemed to await us. Poor mortals! How shortsighted are we! And when, poor easy fools, our happiness is ripening, a dart from heaven drops down and breaks our rest forever.

I had only been a wife three months when a dream warned me of my fate. Methought I came into a room and found my husband and his brother with swords drawn, ready to destroy each other. I gave a scream and ran between them, crying out, “Is there no other way?” “Must brother fight brother?” my husband replied, “No other way, no other way.” I left him to call for help. When I returned I found him on the floor desperately wounded…At this moment my husband awakened me. “What is the matter,” said he. “Surely some frightful dream has disturbed you.” My pillow was wet with my tears – my senses had fled – I knew him not. I could not believe he was beside me – the horror of the vision seemed to rest upon my heart. When I was able to repeat it he said, “I have always told you that my happiness is not lasting. It has no foundation. Let us enjoy it as long as we may and leave the rest to God.”

And we did enjoy it, blessed with parents, brothers, sisters, friends. No table was so surrounded; it was the feast of reason and the flow of soul. We had peace and plenty in our land. War was the dream we thought of.

To say how this war commenced would be needless any further than it respected my situation…It broke out two years after my marriage…and unfortunately for me my husband was named by the Committee as Brigadere General although in N. York.

With some surprise I saw Schuyler with a cockade in his hat and after he had left us my husband took a black ribband and with a half smile requested me to tie it up for him. I felt a stroke at my heart as if struck with lightning…”Be calm,” said he, taking my hand. “Listen and you to what I have to say…Honour calls on me. And surely my honour is dear to you yet, with you I leave this point – say you will prefer to see your husband disgraced and I submit to go home now to retirement.” Alas, what now could I say to such an appeal. I was silent. I took the fatal ribban. He thanked me. My tears did not flow the less.

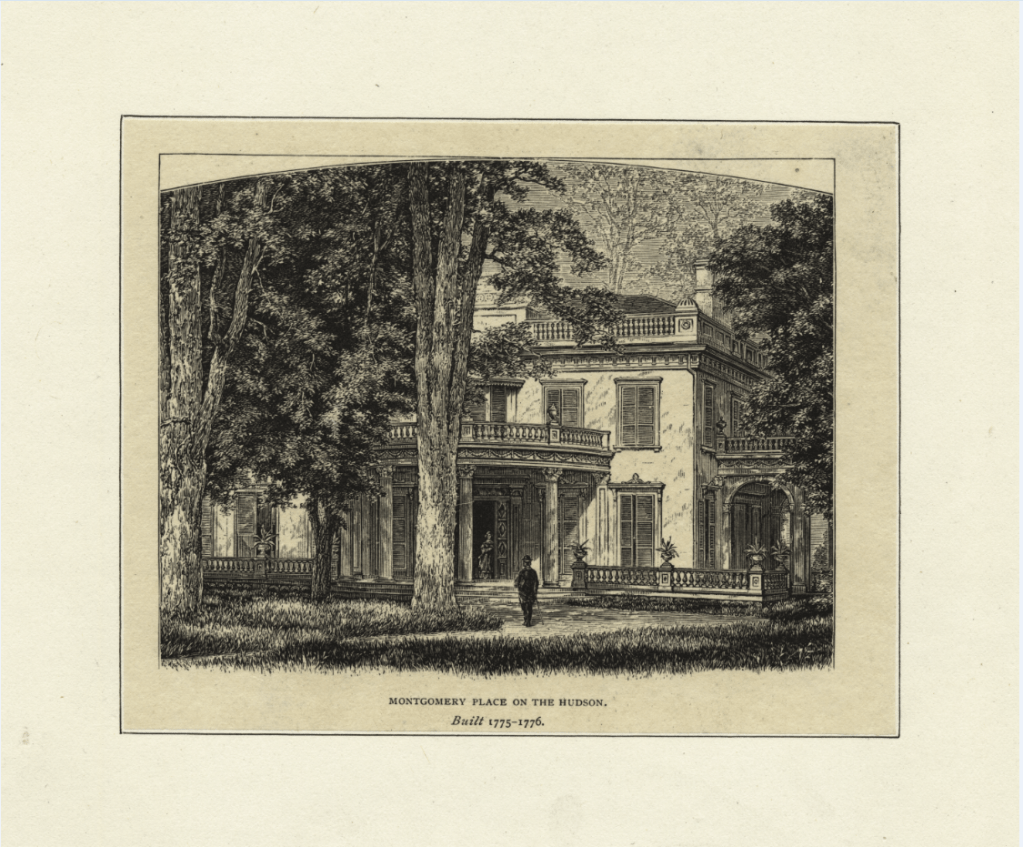

The parting between Janet and Richard became permanent when he was killed in Quebec in 1775. Janet became revered as “The Nation’s Widow” and was granted a seat at all society functions. She never remarried and she spent the rest of her days until her death in 1828 living at her home called Montgomery Place. There she was surrounded by family, farmland, and fruit. Janet’s story is one of lost love but it is also one of a quick-witted, confident, and strong young woman who came of age during a pivotal time in American history. And it’s been an honor to have her as a guest writer on the Lives of Livingston Ladies Blog Series.

Leave a comment