Margaret Beekman Livingston was born on March 1st, 1724 – meaning Happy Belated 301st, Margaret! After losing her mother at a young age, Margaret’s father, Henry Beekman, sent her to live with an aunt in Brooklyn. The idea of a widower raising a daughter alone was not socially acceptable in the Colonial Era (nor by the later 19th Century when John Henry loses his first wife). While Margaret’s father wasn’t necessarily equipped to raise her without a woman in the house, he made sure Margaret received a well-rounded education. Rather than learning only how to take care of house and home, Margaret learned how to help her future husband with finances and business matters. She, like many Dutch women of the time, was taught to be a partner in every sense of the word – something not seen with English women at the time.

In 1742, when Margaret was just eighteen years old, she married Robert Livingston (known as Robert the Judge) at Clermont. Children soon followed, eleven in total and ten surviving into adulthood – an impressive statistic for the time. This meant Margaret and Robert had kids in the house consistently over the span of twenty years. Margaret wrote of the affection between the siblings saying, “never did three estimable brothers and six sisters love each other better than they do”.

Margaret and Robert’s marriage was rare for the time. While the union had been arranged by their wealthy families, the two were a true love match within the Livingston Family history. In 1755, Robert wrote to Margaret, saying:

“To you I am not used to disguise my thoughts. Indeed, I have for a long time been generally sad, except when your presence and idea enliven my spirits.

You are the cordial drop with which heaven has graciously thought fit to sweeten my cup…My imagination paints you with all your loveliness…I may truly say, I have not a pleasant thought (abstracted from an hereafter) with which your idea is not connected…”

In addition to viewing Margaret as an excellent wife and mother, Robert also sought her guidance and opinion regarding business matters. He knew she had received a thorough education and possessed essential acumen to assist him with the running of the Clermont estate. That knowledge would come in handy when Margaret found herself suddenly widowed in December of 1775.

One day after their 33rd wedding anniversary, Robert the Judge passed away after a brief illness. Margaret was devastated by the loss and wrote about how objects in their home would fill her with grief and thoughts of her lost love. Despite Clermont becoming a place of mourning, the Revolutionary War was raging, and Margaret was witnessing its effects on her many children. Her eldest daughter, Janet, became a widow in the same year as Margaret herself. Robert the Chancellor, her eldest son, was deeply involved in the American government’s bid for independence and her younger sons, Henry and John, were involved in the war effort in military roles. At the same time, four children remained at home, along with Margaret and her staff of paid servants and enslaved people.

The truest testament to Margaret’s resilience came in the fall of 1777 when British soldiers, after burning Kingston, New York’s capital at the time, came to Clermont to burn the Livingston home. Stories through the years have featured Margaret hurrying everyone onto carts and wagons and racing away from the burning house and the hostile British army. In reality, Margaret had enough warning to make a plan; she left in advance of the British arrival and sought shelter at a relative’s home in Salisbury, Connecticut. She prioritized saving sentimental belongings, including her and Robert’s wedding portraits.

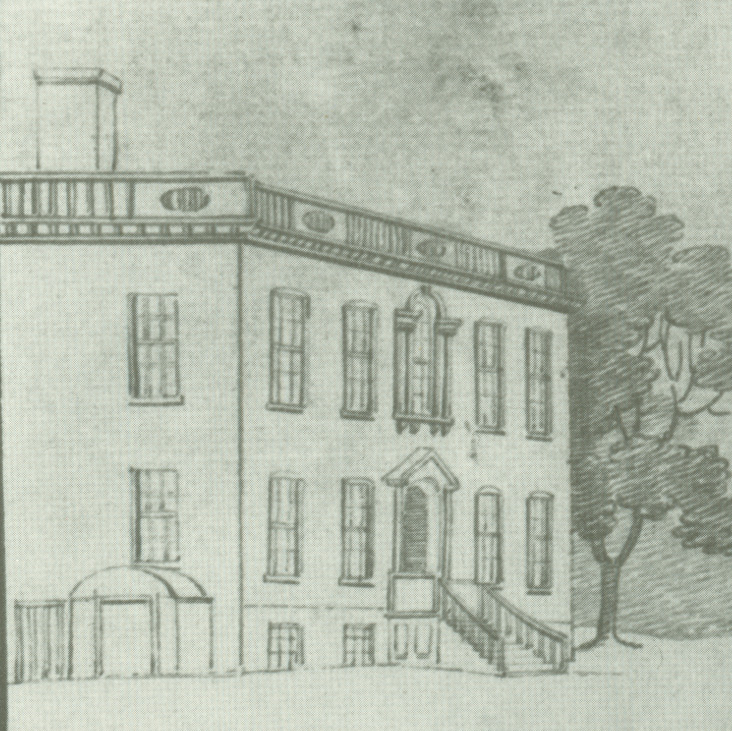

A few months after the British attack, Margaret returned to Clermont and found her home – the home in which she had married her beloved and raised her children– burned to the ground. It would have been easy to return to Connecticut and await the war’s end before making plans to rebuild Clermont, but Margaret Beekman Livingston was never one for “easy”. After having the foundation cleared by enslaved people, Margaret began a letter writing campaign to Governor George Clinton. She requested the release of local architects from their militia obligations so that her home could be rebuilt. She was, understandably, denied the request. However, with her perseverance (and her wealth and family name), Margaret was eventually able to convince Governor Clinton to acquiesce. Her home was rebuilt, on the original footprint, by 1783.

There can be no denying that Margaret Beekman Livingston possessed immense privilege to be able to request and finance the rebuilding of Clermont. What makes Margaret impressive is the fact that, as a woman of the time – a widow with young children, no less – she possessed the tenacity and the confidence to lobby the governor of New York until she received the resources she required. Her perseverance is one of the main reasons Clermont stands today.

Margaret’s devotion to her family and this house continued on until her death in 1800 at the age of 76. She even died within Clermont’s walls (not IN the walls like a Poe story, just in the house). With all of that in mind, Margaret Beekman Livingston, the tenacious matriarch who had Clermont rebuilt is the clear choice to kick off this blog series featuring strong, creative Livingston women in honor of Women’s History Month.

Leave a comment