“When I first came to this House it was late in the Afternoon, and I had ridden 35 miles at least. “Madam” I said to Mrs. Huston, “is it lawfull for a weary Traveller to refresh himself with a Dish of Tea provided it has been honestly smuggled or paid no Duties?” / “No sir, said she, we have renounced all Tea in this Place. I cant make Tea, but He make you Coffee.” Accordingly I have drank Coffee every Afternoon since, and have borne it very well. Tea must be universally renounced. I must be weaned, and the sooner, the better.”

John Adams in a letter to Abigail Adams, 6 July 1774

The coffee urn pictured above in the dining room at Clermont dates to about 1780 and it was produced by a British manufacturer in Sheffield, England. It is made from silver-plated copper, and engraved with the initials “R.R.L.,” most likely in reference to the Chancellor Robert R. Livingston. We don’t retain a lot of specific information or family stories about this vessel, but we do know that it was used to hold coffee – a commodity which was politically activated throughout the 18th century and embodied, and still embodies, an important colonial history.

Preference for coffee over tea and coffeehouse culture over teahouse culture parallelled the revolutionary effort in the 18th century. It was a potent political choice and a clear indication of personal loyalty. The Boston Tea Party in 1773 is the most well-known example of the political symbolism applied to the consumption of this commodity. This event marked a clear cultural separation away from tea and the British empire. After the war, the political significance of drink preference lessened and Americans, including the governing class, enjoyed both coffee and tea again.

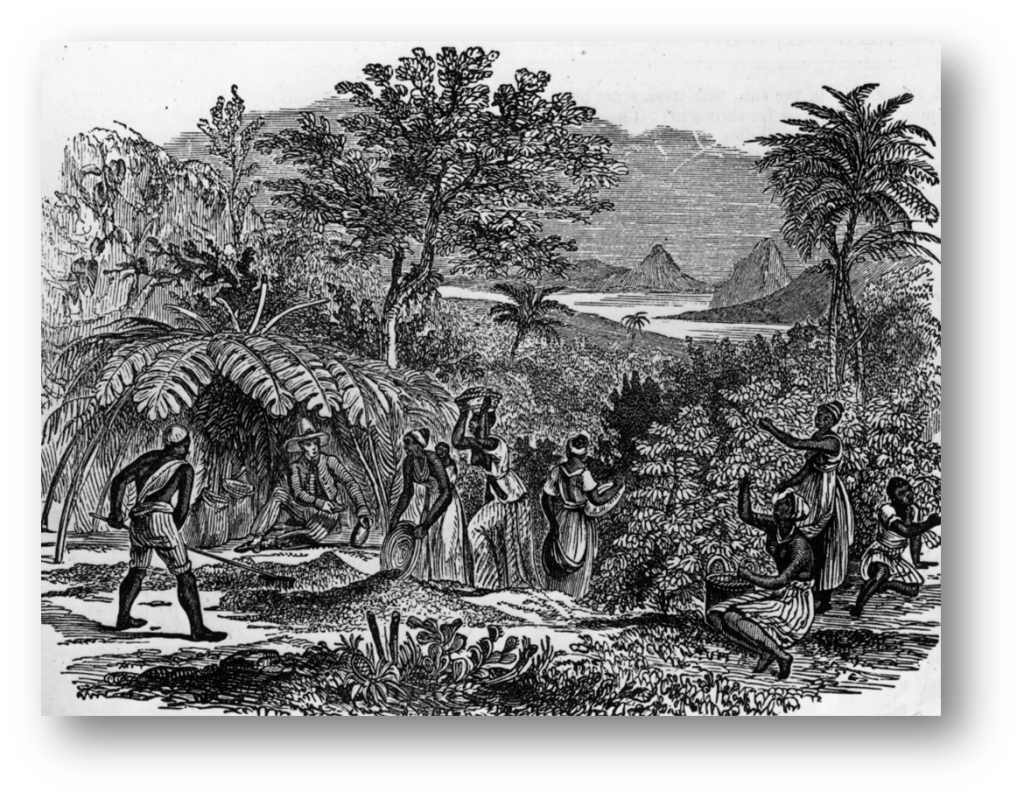

Coffee made its way into 18th century colonial America through the transatlantic trade system. The Dutch began circulating arabica coffee beans from Ethiopia as early as 1650, which initiated the incorporation of coffee within 17th century plantation systems. Importantly, coffee was cultivated by enslaved Africans, primarily from west Africa, by colonial powers such as the Dutch and the British, in colonies from Suriname to Jamaica. The labor of these enslaved peoples forced to work in these colonies is what enabled coffee to become a staple commodity in transatlantic trade and in colonial America.

Because coffee required some skill and specialized preparation to be made enjoyable, such as specific roasting requirements and grinding equipment, most people went to coffeehouses to get their fix. Coffeehouses became spaces for consumption as well as for socializing and political and intellectual discussion. Additionally, coffeehouses became centers of trade and commerce, for those looking to sell or procure commodities. In short, coffeehouses became incubators for revolutionary thinkers and ideals across social classes – although, predictably, these spaces excluded women and minorities.

John Adams, the second president of the United States, wrote of visiting coffeehouses with his contemporaries, such as Benjamin Franklin, to discuss colonial politics and wrote of the importance of renouncing tea in favor of coffee for the revolutionary effort. In fact, Adams owned an engraved silver-plated urn, very similar to this one owned by the Chancellor, which was, ironically, produced by a British manufacturer in Sheffield. It is said that, although the urn was originally made for tea, Adams likely used it for coffee instead. Interestingly, this urn was also made in Sheffield and used for coffee rather than tea so we can assume that the Chancellor’s attitude towards British commodities and his consumption of coffee throughout the Revolution was at least in part political and in line with Adams’s well-documented views. This choice, especially factoring in the British provenance of the Adams and Livingston coffee urns, further illustrates the trend of consuming specific commodities while eschewing others as a political statement of resistance in America during this time.

Coffee remained popular even after the Revolution when Americans began drinking tea again. Adams and Jefferson both retained their preference for the drink and brought the beverage into the White House, making it an essential element in the daily refreshments that were served. With this in mind it is important to consider that the coffee the governing class drank, from Washington to Livingston to Jefferson, was cultivated as well as prepared and served by enslaved people, who were forced to labor alongside free Black and white servants. So, while this vessel symbolizes an important socio-political history, by considering the material history of coffee we are also able to identify and acknowledge the layers of enslaved labor, from the immediacy of the enslaved staff who was responsible for the preparation and serving, such as the Chancellor’s own enslaved staff, to the broader circle of enslaved laborers in the colonies and plantations – all of whom enabled the cultivation and consumption of this product.

Leave a comment