“The ideal of the artist is to materialize [her] thought, in a splendid form. [Alice] strives for this and achieves it through her sincerity and the depth of her conception.”

– Revue du Vrai et du Beau, 1928

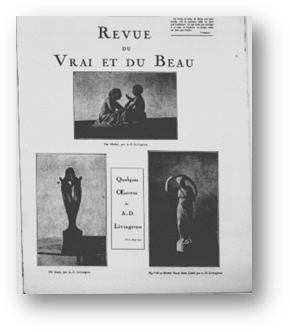

In July of 1928, Revue du Vrai et du Beau published a short article on a selection of sculptures by Alice D. C. Livingston accepted for display at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts that year. Although relatively short, this is the only published piece we have been able to find on Alice’s work and her exhibition history as an artist. Finding any publication on her work, especially one contemporary to the time in which she was actively making and showing her sculptures, is fortunate considering she was a self-taught artist and came into her visual art practice later in life. From oral histories as well as her own recollections and albums, we know that Alice began to sculpt in 1925 at the age of 53, at which point her two daughters were in their mid-teens. Revue notes this, stating that her late start in sculpting, or “modeling,” was due to her occupation with society and family. Interestingly, rather than labeling her an amateur, they praise her work as original because of the unique viewpoint and technique she developed through the process of teaching herself to sculpt. This is unusual in that her seemingly marginal position as someone who was not trained within the conventions of the academy is viewed as a strength rather than an indication of inferiority: “…all figures [have] an intensity of life, a purity of lines, a delicacy of model and a harmony of proportion which testify to the virtuosity of talent, in full possession of a very personal technique…Having never had the leisure to take lessons or follow courses, she was her own teacher, hence, no doubt, this note of personal originality that I am pointing out” (Revue, 15, 16).

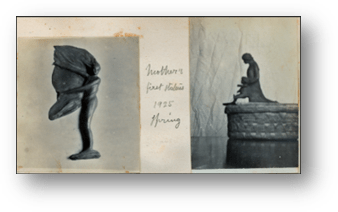

Much of the body of the Revue article is dedicated the bronze figurine pictured and labeled “The Scarp” on the summer edition’s title page. A loose translation of the original French describes the bronze statue, which depicts a draped female figure, as one of “mystical appearance” imbued with spirituality and symbolism: “…so much does the spiritual, the idea, the symbol, dominate…It becomes a soul, lifted towards infinity, the body…is nothing more than a grand envelope for thought” (Revue, 15). Today this statue is on display in Clermont’s library, tucked between an elaborate 19th century candelabrum and an Italian flower urn. Known to Clermont staff as “Isis,” a subject likely influenced by Alice’s appreciation of Egyptian sculpture and line, it cannot be overlooked that this piece is titled differently in the pages of Revue. After examining the physical object itself, I discovered a label affixed to the underside of the base written in Alice’s hand which provided two titles for the statue: “Isis” and “My Veil no Mortal Hand Hath Lifted.” Based on this information, I believe it’s likely that the editors of Revue labeled the photographs of Alice’s statues incorrectly on the title page considering that the sculpture pictured adjacent to the bronze is the one labeled “My Veil no Mortal Hand Hath Lifted.” This second sculpture depicts another female figure draped in a sleeveless dress and winding a long, delicate cloth around herself. Additionally, the bronze in question is referred to in the body of the article as “My Veil….” Taking all of these details into account, I suggest that the title “The Scarp” was intended for the second sculpture and that, possibly, it was supposed to be titled “The Scarf,” in reference to the long, thin shawl that the figure is in the process of wrapping around herself. While we do not retain this particular piece in Clermont’s collection, a framed photograph of it is displayed in a cabinet in Clermont’s study alongside a selection of Alice’s sculptures, including “The Mother,” also pictured in the article and exhibited in 1928.

Despite the fact that Alice’s work was mistitled in the publication, the article itself provides valuable insights into the reception of Alice’s work among potential patrons and collectors in the art world in the late 1920s: “The works of this artist were acquired by connoisseurs from Europe and America and one of the officials of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence is of the opinion that the works of Alice Livingston could be compared to the Tanagra” (Revue, 16). Although the details of these acquisitions are not provided, that her work was acquired at all indicates a positive reception among a varied group of patrons, collectors, museum officials, and potential buyers during this time. Additionally, it is telling that officials from institutions as renowned as the Uffizi saw fit to stop and discuss her sculptures. The “Tanagra,” in which her pieces are compared, refers to a specific type of terracotta figurine which gained popularity in the latter quarter of the fourth century B.C.E. These statuettes were “appreciated for their naturalistic features, preserved pigments, variety, and charm…[and were] based on an intimate examination of the personal world of mortal women and children…” (“Tanagra Figurines,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art). Like the Tanagra, Alice’s work depicts delicately posed female figures, often hand painted and classically draped, as well as intimate moments between women and children. It is thanks to this article, and the unnamed official from the Uffizi that we are able to consider the similarities of visuality and subject matter between Alice’s work and this form of ancient era collectable sculpture. And, overall, this article provides valuable insight into the exhibition history and public reception of Alice’s work in the larger art world at the end of the 1928, a mere three years after she taught herself to sculpt.

Leave a comment