On April 20, 1818, an old man stood outside City Hall in Hudson having just arrived from Germantown. He was 76 years old, and he was there to apply for a pension for his service to the United States during the Revolutionary War. Like thousands of other veterans around the country he was waiting for his time in front of a judge and a clerk to give his story in the hopes that the government would grant him some money.

His turn came. Perhaps he tried to stand up straight with the martial bearing he had had thirty-five years before. Or perhaps a hard life left him shuffling into the court room. He swore to tell the truth on the bible then began his story.

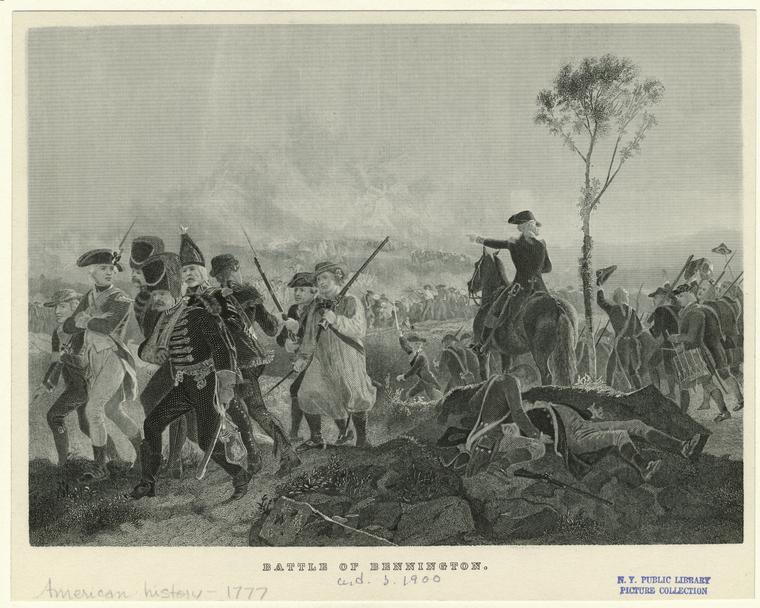

His name was Christopher Loyer and he belonged to the British army at the Battle of Bennington. He was part of the German corps commanded by Freiherr Friedrich Adolf Riedesel Freiherr zu Eisenbach.

The judge must have been incredulous. Why would a Hessian think he deserved an American pension?

Loyer continued. Immediately after the Battle of Bennington, which occurred on August 16, 1777, he deserted from the British Army and turned himself over to the American Army. He was, perhaps purposefully, vague about participating in the battle.

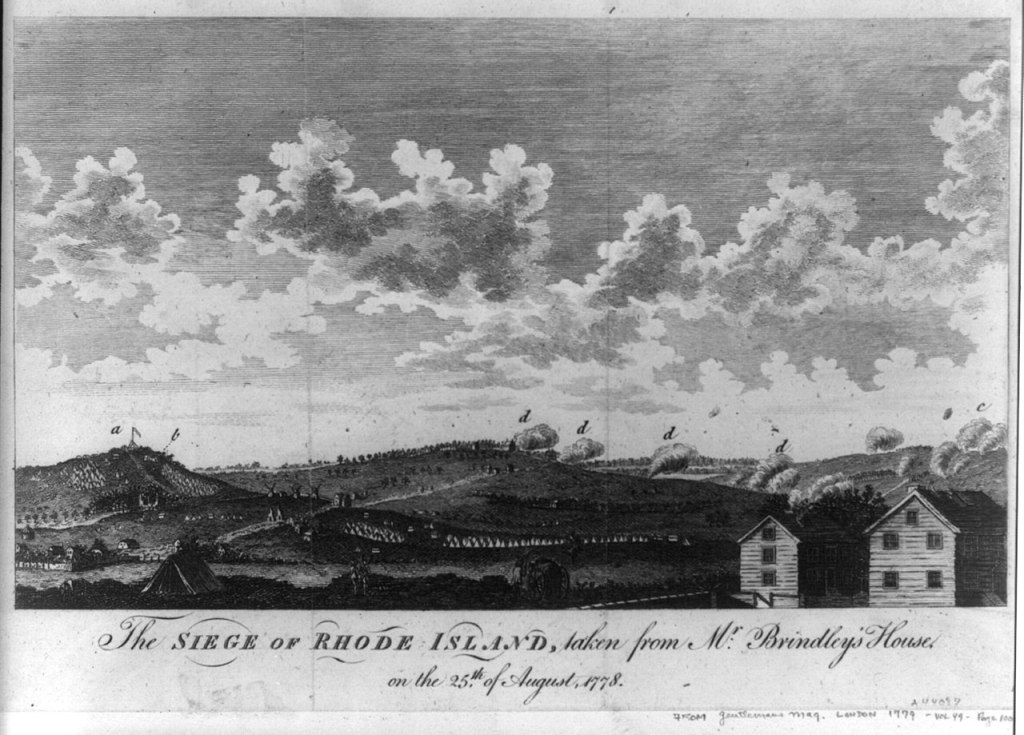

Loyer was taken to Albany, where a few weeks later he enlisted in Colonel James Livingston’s 1st Canadian Regiment. Livingston was the grandson of Robert “The Nephew” Livingston, who came to America to help his uncle Robert “The First Lord” Livingston run his business empire. Livingston’s regiment took part in both Battles of Saratoga, though Loyer does not mention these fights in his testimony. He does mention the Battle of Rhode Island two years later, where Livingston’s regiment fought against the British for control of Newport, Rhode Island. Despite the best efforts of General John Sullivan and his men the battle was doomed to failure after the French had pulled their support for it.

In 1781 New York reorganized its army regiments and Livingston’s Regiment became part of the 2nd New York Regiment. Later that year they marched with George Washington to Virginia where they helped capture General Charles Cornwallis and his army at Yorktown. Loyer was in the trenches.

Loyer returned north and was encamped at Newburgh. He was discharged from there in the spring or summer of 1783.

Loyer could not sign his testimony. Instead, he marked it with a shaky “X”

Loyer was awarded his pension. Unfortunately, life did not get easier for the old soldier. He was back in court in 1819 hoping to get his pension increased. The now 77-year-old, who had now moved to the town of Livingston, testified that he had no trade or occupation, he had no relatives in America, and except for his pension, depended on charity to get by. He could not contribute to his own support at all.

And that’s where the record ends. It remains unknown if Loyer got his increased pension or for how much longer he lived. There is no record of a grave for the Hessian turned patriot.

Leave a comment