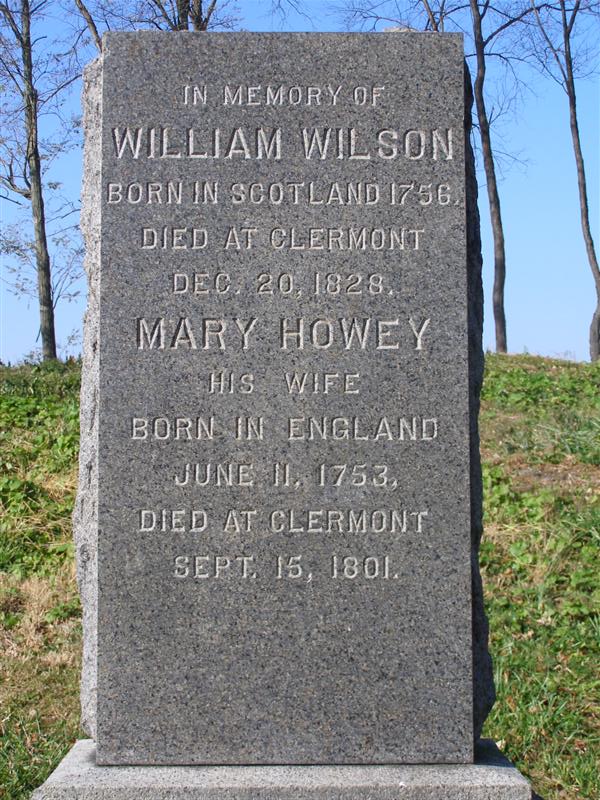

William Wilson was born in 1756. Where is a bit of mystery. Some sources have him born in Scotland, other sources list his birth place as Wooler, Northumberland, England, which is very close to the Scottish border. His father was Reverend Alexander Wilson, the presbyterian minister for Wooler.

William graduated from the University of Glasgow in 1775 or 1778 and followed his father into the ministry. His time as a minister was short however and he soon left to study medicine, possibly because of a disagreement with his father. It’s unclear where Wilson studied medicine but if he could afford it he certainly would have studied at the University of Edinburgh, which was not only nearby but also one of the most respected medical schools in the world at the time. In 1781 he married Mary Howey in the church of England in Durham. This shows that his disagreement may not have just been with his father but with the presbyterian church itself. They soon had two sons, one who survived and one who didn’t,

In 1784 Wilson left England and came to America, heading straight for Clermont. It would take another two years to get Mary and his son to follow him. Mary’s father did all he could to keep his daughter and grandson from leaving, Withing weeks of arriving at Clermont Wilson was practicing medicine.

Wilson’s practice thrived. Not only was he the Livingston’s choice for doctor but he saw patients between Red Hook and Hudson and even crossed the Hudson River to see patients in Catskill and Saugerties.

Wilson’s patients ran the full gamut of the social spectrum. A visit to Clermont may have meant visiting the Chancellor and his wife marry but also one or more of their enslaved people. Farmers, millers, servants, the rich and the enslaved all received equal care from Wilson. His main patient in Catskill was Dr. Thomas Thomson, the former doctor of Livingston Manor, so Wilson’s skills must have been up to par.

Most of Wilson’s patients would pay him at the time of treatment, usually in money but sometimes in goods, if they were short on cash. Some even had an early form of health insurance with the doctor. An individual could pay the doctor a fee up front for medical care for a determined amount of time. If they didn’t need much healthcare during that time the doctor made a nice profit, on the other hand if the patient became sickly it could end up costing the doctor money. For example, on August 18, 1788 Wilson agreed to provide health care for a man named Heermance of Clermont for three years for the sum of £50.

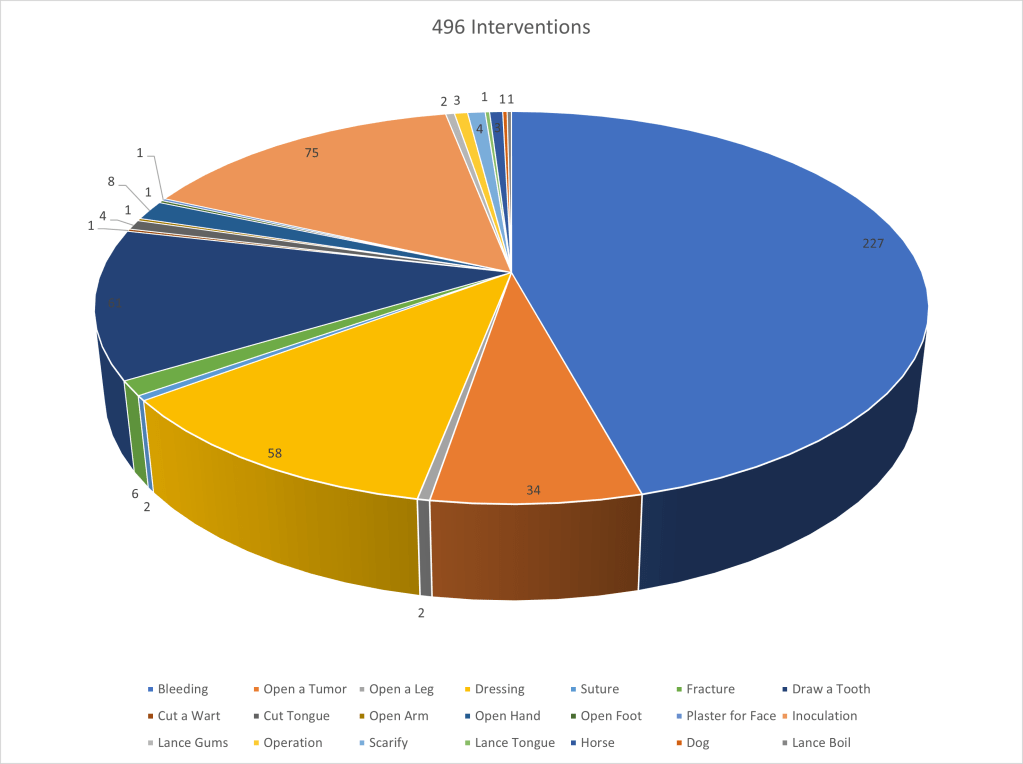

During this time Wilson’s most common medical tactic was some kind of medicine. Nearly every patient he visited was left with a medicine of one kind or another, so much so that he rarely listed the types of medicines he was given in his day books. The next most common treatment was bleeding which was still popular at the time. It was thought to balance the humors and was used to treat any number of illnesses. Medicine to induce vomiting or defecation were also used for the same reasons. Other treatments that Wilson carried out during his time as a practicing physician included opening and removing tumors, dressing wounds and setting broken bones. He was even called upon to visit a horse or a dog, a time or two.

Wilson was a major advocate for inoculation against smallpox. This involved introducing the pus from a smallpox pock into a small cut on the patient’s arm. This generally led to a very minor case of the disease, that once recovered from provided immunity from it in the future. The mortality rate was much lower than catching smallpox the “natural” way. During his time as a doctor, Wilson conducted at least 75 inoculations including Chancellor Livingston’s household.

Wilson was the attending doctor at the end of Chancellor Livingston’s life. After Chancellor Livingston suffered his first stroke, Wilson consulted with doctors from Albany, bled the Chancellor and tried several medicines. Despite his best efforts the Chancellor passed away. On February 25, 1813, Wilson wrote in his daybook, “N,B. Mr. L. died Thurs. evening 6 o’clock bur Sunday 2.28”

Earlier Wilson had become close to the Chancellor. He acted as the Chancellor’s estate manager while the Chancellor was in France and continued the role when the Chancellor returned. When the Chancellor died, he was the executor of his will and became a close confidant of Edward Livingstons.

On a personal note Wilson’s wife Mary passed away in 1801. After a long widowerhood, Wilson remarried to Hannah Shufeldt, 28 years his junior, in 1820.

While livings in Clermont Wilson rose in society. He helped to found the Medical Societies of Columbia and Dutchess counties. He served as vice-president of the Agricultural Society of Dutchess County and sat on the Board of directors of the Highland Turnpike Company. He was the postmaster of Clermont and was elected a county judge.

After a long life of service to others Wilson died on December 18, 1828. He was 72. He was buried in the Clermont Cemetery behind the modern Clermont Town Hall.

Leave a comment