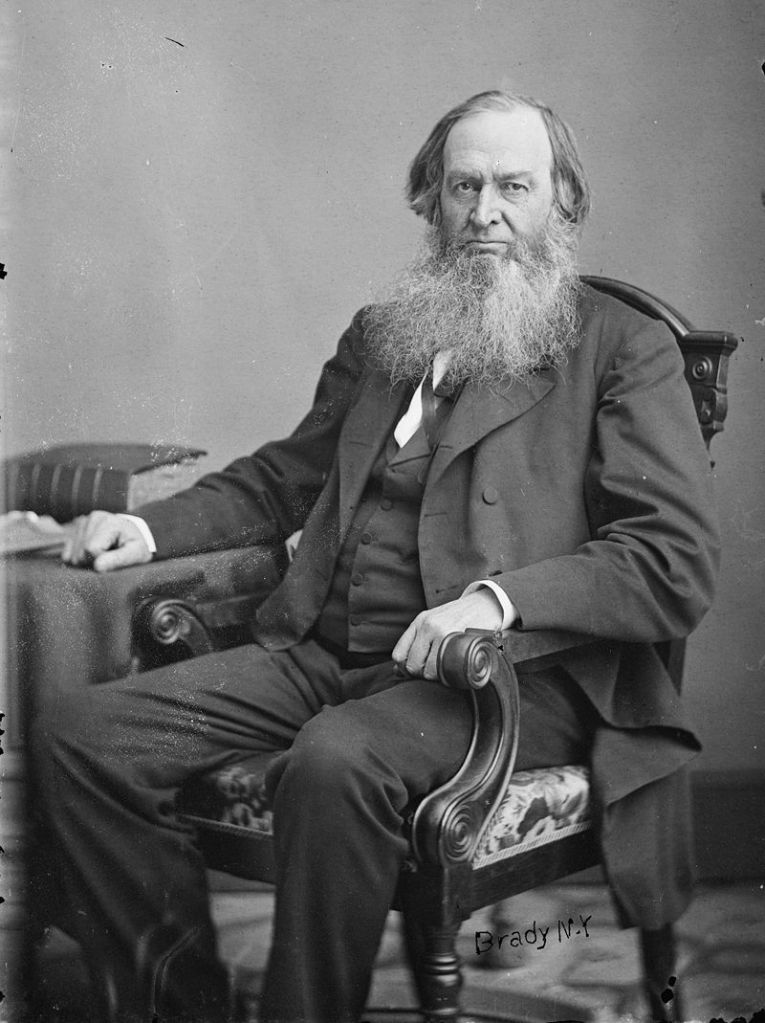

Gerrit Smith was born on March 6, 1797. And yes, before you ask, he was a Livingston. Through his mother, Elizabeth, he was the great – great- grandson of Robert “the nephew” Livingston. Robert “the nephew” was the son of Robert Livingston, the First Lord of Livingston Manor’s brother James. The younger Robert arrived in New York in 1687 to help his uncle with his business dealings.

Gerrit’s father, Peter Gerrit Smith, was a very wealthy man. He bought 50,000 acres of land from New York State that the state had essentially stolen from the indigenous people who had lived there. He called his new tract of land New Petersburg. The headquarters of the tract was Peterboro, about 30 miles west of Utica, where he built his home and land office using enslaved labor. The elder smith owned four enslaved people but sold them once construction on his home and office was completed.

Gerrit’s mother died the day after he graduated from Hamilton College in 1818. His father soon felt the need to move away and sold his home and land to his son for $225,000. By selling land in the tract and acquiring new land elsewhere, Gerrit not only paid his father off very quickly but became one of the largest land holders in the state, eventually owning land in 54 New York counties (out of a total of 62).

Gerrit was a reformer from his earliest days. Two of his early causes were an end to enslavement and temperance. In 1824 he claimed to have given the first temperance speech to the New York State legislature. He even open a temperance hotel in Peterboro. This ultimately proved to be unpopular and closed within a few years of opening. He also supported women’s rights. Not just women’s suffrage but the idea that women deserved to be completely equal to men. He frequently met with his first cousin, and fellow Livingston descendent, Elizabeth Cady Stanton on the issue. His daughter Elizabeth Smith Miller was active in the dress reform movement and the women’s suffrage movement.

In the 1820’s Gerrit was a colonizationalist. The movement sought to send free born black people and freed enslaved people to Africa. The American Colonization Society wheedled land out of native African people in order to create Liberia as a colony for the people they sought to send to Africa. The capitol of the colony was Monrovia, named after James Monroe, who supported the effort. Gerrit broke with the movement in the early 1830’s when he realized that the movement was not a true abolitionist movement. At one point he simply began buying people and whole families out of enslavement in the south and freeing them.

Gerrit felt that education was key to formerly enslaved people. He thought education would help them claim a place equal to white people in society. As such he opened a school for Africa-Americans in Peterboro in 1834. Right about the time that he helped to found the Liberty Party. This political party would be a driving force for complete abolition leading up to the Civil War. Gerrit also financially supported many institutions of learning which taught black students or integrated student bodies. These included The Oneida Institute, Oberlin College, New York Central College, Berea College, and Howard University. He had also supported schools in Liberia before his break from that movement. He also refused to support schools that did not teach the bible believing that was an important tool in advancing people. On the other hand, he believed that the sectarianism of Christianity was a sin and started his own non-sectarian church. Gerrit also refused to support the Erie Canal.

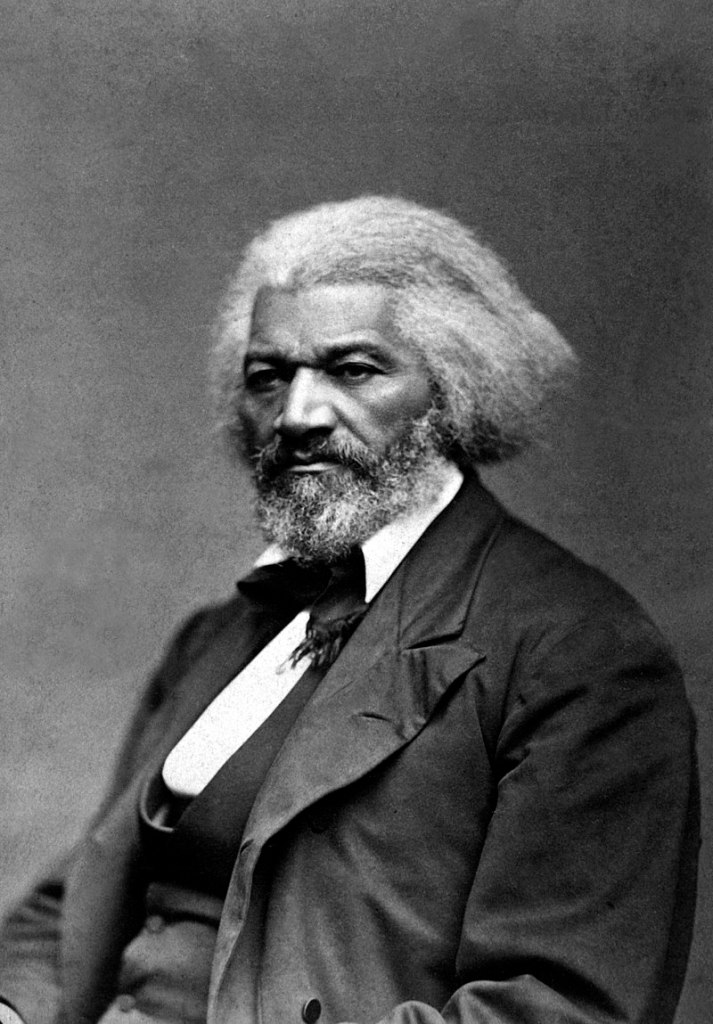

Gerrit had a great friendship with Frederick Douglass. In addition to financially supporting Douglass’ news paper The North Star, Gerrit and Douglass’ organized a convention for freedom seekers, formerly enslaved people who had escaped bondage in the south and headed north. The meeting was initially scheduled to take place at Peterboro but grew to large and had to be moved to nearby Cazenovia. As a side note, Gerrit had opened Peterboro as a stop on the Underground Railroad for these freedom seekers. The conference that Gerrit and Douglass’ organized was in protest of the Federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In addition to his direct support of the Underground Railroad, Gerrit also financially supported several efforts to break captured enslaved people out of jails before they could be returned to the south.

Its easy to assume that a man as reform and public service minded as Gerrit Smith would have political ambitions. He, however, had none. There were others that felt he would make a good politician. He was nominated for president four times, governor 3 times. He was elected to Congress for one term but resigned after one year.

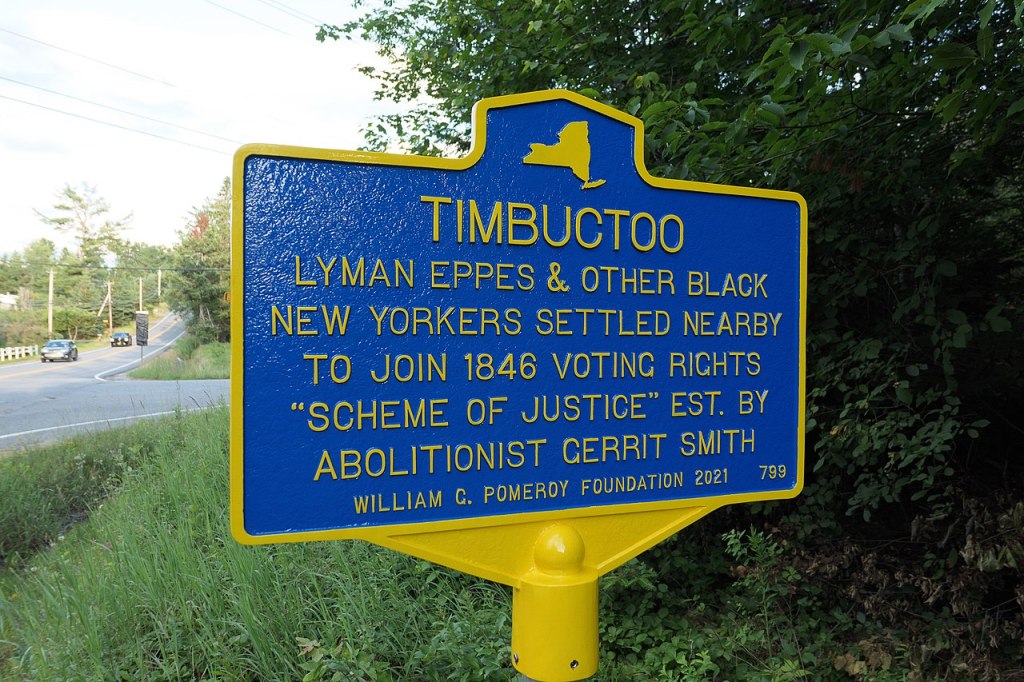

Gerrit was a major believer in land being a great equalizer. For one thing owning $250 worth of real estate in New York gave anyone the right to vote. He donated and gave a great deal of land to people through out his life for this purpose. In 1848 his most ambitious project began in the Adirondack Mountains. It was called Timbuctoo and involved Gerrit hoping to give 3,000 families part of 120,00 acres of land. Not only would owning land elevate the people but he hoped to attract black people from urban environments, where they were much more likely to run into fugitive slave hunters. Unfortunately, only 50 black families took Gerrit up on his offer. The idea was good on paper but failed in practice. The land was not good for farming, winters in the Adirondacks are incredibly harsh and rather than being a tight knit community the land that Gerrit was offering was spread out over forty square miles. The black families also faced intense racism and resentment from the area’s white settlers.

Perhaps the most famous of the areas residents was John Brown, who bought a little over two hundred acres of land from Gerrit in 1849 for the rock bottom price of $1 an acre. John Brown’s farm, now a state historic site, is the only structure still standing from Gerrit’s attempt to settle the Adirondacks. https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/johnbrownfarm/amenities.aspx

Gerrit financially supported Brown’s move to Kansas in 1855 to help bring Kansas into the Union as a free state. During his time there Brown would lead an attack on sleeping pro-slavery advocates which saw five men slaughtered with swords by Brown, his sons, and their supporters.

In 1856 Brown returned east and traveled through New England trying to gather support for his next action. Eventually, five men from Massachusetts and Gerrit, who became known as the “Secret Six” gave money to Brown for his attack on Harper’s Ferry.

When Brown’s mission predicably failed and he was hung for treason, Gerrit had a mental breakdown. Perhaps he feared that his part in the plot would be discovered, and he would be next on the gallows or perhaps he was simply worn out from all his activity. He was institutionalized briefly and treated with cannabis and morphine.

With the Civil War rapidly approaching Gerrit began to acknowledge that violence and blood shed might be necessary to bring about the end of slavery. Gerrit had been a long-time supporter of a gentle approach to the south, even giving speeches about compensation slave holders for their enslaved people upon them being freed.

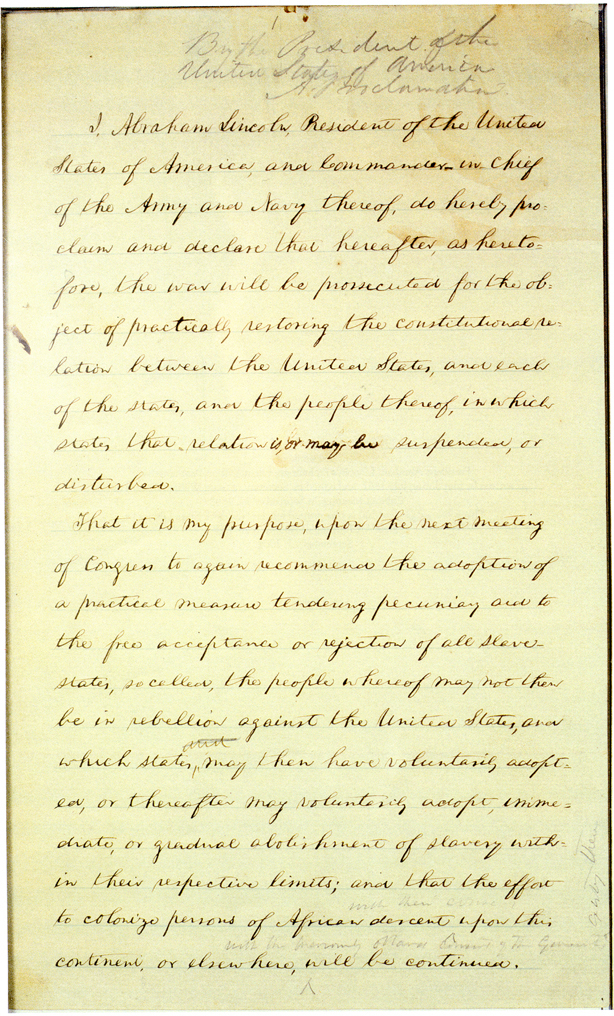

During the war, Gerrit of course supported America over the traitors in the south. In one lottery used to raise money for the war effort, Gerrit won Abraham Lincoln’s original handwritten draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. He donated it to New York State. Today the fragile document is occasionally displayed at the New York State Museum or the New York State Capitol.

With the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the United States. Gerrit urged a gentle touch with the south and not blind retribution on the traitors who had attacked their own countrymen. To that end Gerrit was one of three men who signed the bail bond that got Jefferson Davis out of jail.

After the war Gerrit continued to give money to people in need and causes that would help bring about equal rights for all people. It’s estimated that during his lifetime Gerrit gave away about $8 million, in 19th century money. Gerrit died of a stoke on December 28, 1874.

Leave a comment