During the American Revolution hundreds of American fishing and merchant vessels had their hulls strengthened, cannons mounted, and their crew sizes increased. With a letter of marque in hand these ships went privateering. These ships attacked British merchant vessels and even small British navy ships. Successfully captured ships were sent back to American ports where the goods they carried were sold or condemned to be used by the American military. The ships themselves were usually sold, if they were still seaworthy, and sometimes even turned into new privateer vessels.

With all these captured cargoes and ships changing hands there was a great deal of money to be had. And of course, it was expensive to outfit one of these vessels for privateering. In addition to the hull modifications and cannons, the ships would need all types of supplies to cruise the seas; gunpowder and shot, food, water and rum, rope and canvas, navigational tools, and an extensive list of other supplies. The money had to come from somewhere. This meant investors.

John R. Livingston, the third son of Margaret Beekman Livingston and Judge Robert Livingston, was a keen businessman and knew a good opportunity when he saw one. The investment wasn’t without risk, if the ship was taken before it took any prizes then the investment was a complete loss, but if the privateer was successful, he could just sit back and let the profits roll in.

We get an early sense of how his investments were working out in a letter to his brother Robert dated October 11, 1776. In it he writes that he had made £800 from his investment in the privateer Beaver which was “much more” than he expected. He rolled that money into an investment in a larger vessel and asked his brother’s help in securing 4- and 6-pound cannons.[i] [ii]

A letter to his brother the following February gives a much clearer picture of the extent of his investment in the privateering industry. He owned:

1/14 of the sloop Congress which sailed out of Boston in October of 1776

1/14 of the sloop Chance which also sailed out of Boston in October of 1776

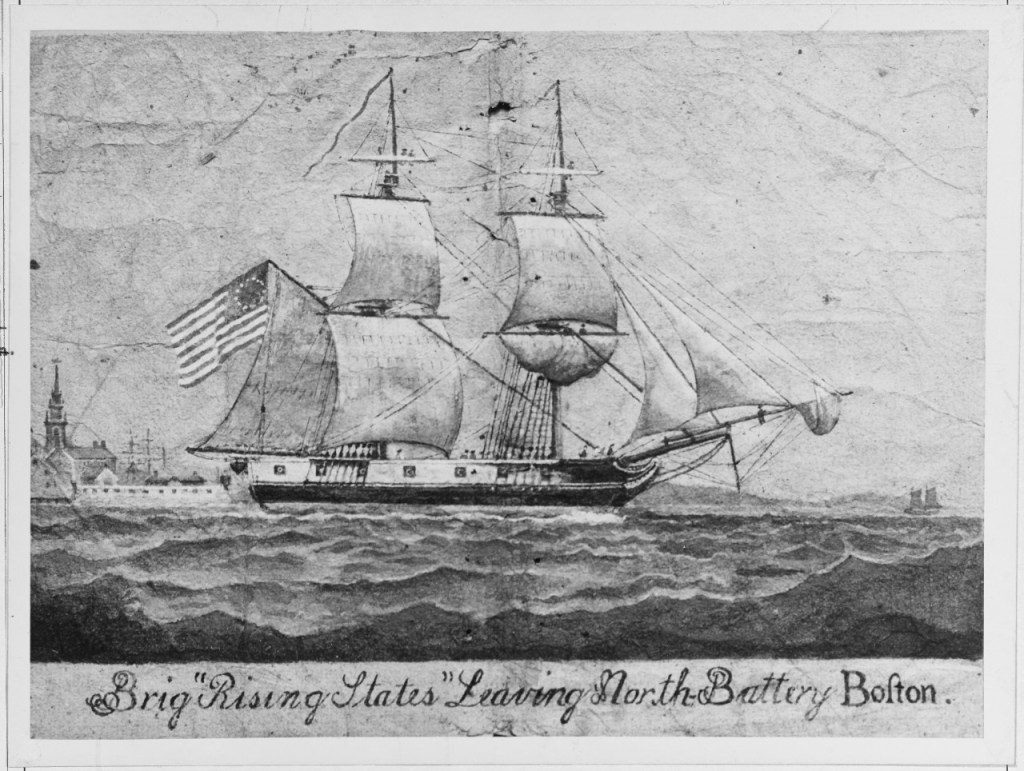

1/12 of the brig Rising States which carried 18 6-pound guns and a crew of 180

1/16 of the ship General Mercer which carried 26 guns and a crew of 250

1/12 of the sloop Beaver

John was considering getting out of the privateering business as he found himself much to invested in it. He figure he had sunk £4882 into the ships.[iii] It is unclear how much, if any, of his investment he was able to divest himself of at this point.

As for the ships that John invested in, they prove to be difficult to track down. The nature of privateers being private property and not property of any government meant that record keeping was minimal.

The best documented vessel was the Rising States. She was originally an American built British transport vessel that was captured, renamed with a patriotic name, and put back to sea as a privateer. Delays in stocking and crewing the ship meant that she did not leave Boston Harbor until January 26, 1777. On March 25, 1777, Rising States took her first prize, the snow Prince George. On April1, she chased another British ship. The ships exchanged feeble gunfire in heavy seas, making most of the gunpowder to wet to fire before the British ship was lost in the weather. On April 3, the brig Fleece was taken as a prize and sailed to France to be condemned. April 12 saw another prize the Holman taken. Rising States luck ran out on April 15, when she fell in with a British ship of the line, the 74-gun Terrible. After a chase, Rising States was forced to strike her colors and was captured. By late 1777 she sold by the British navy and was being fitted out as a privateer again.[iv]

In her brief career as a privateer the number of prizes she took probably made her profitable, meaning the investors would have made a tidy sum for themselves.

The only other record of one of John’s ships is a letter to Benjamin Franklin in 1778, noting that the General Mercer had departed Spain bound for New England. How successful she was as a privateer is unknown. [v]

John R. Livingston was invested in a handful of privateers during the war in addition to his many other business ventures which included selling gunpowder, hand grenades and wine. Privateers were one of the keys to American victory in the war. They made it prohibitively expensive for private vessels to sail to North America, they troubled British convoys to the point that valuable British naval ships had to be diverted from fighting the French, Spanish and Dutch navies to protect merchant ships from the privateers, and they nearly destroyed the Newfoundland fishing industry which was one of the most profitable parts of the British colonial system. Without the hundreds of privateer vessels and thousands of men who sailed on them, its entirely possible that the war would have been prolonged if not lost all together.

[i] A 4-pound cannon fired a cannon ball weighing 4 pounds and a 6-pound cannon would fire a ball weighing 6-pounds. The guns themselves weight hundreds of pounds.

[ii] https://ndar-history.org/?q=node/8331

[iii] https://ndar-history.org/?q=node/10433

[iv] https://www.awiatsea.com/Privateers/R/Rising%20States%20Massachusetts%20Brigantine%20[Thompson].pdf

[v] “To Benjamin Franklin from John Emery, 11 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-26-02-0060. [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 26, March 1 through June 30, 1778, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1987, p. 89.]

Leave a comment