Chancellor Robert R. Livingston died on February 25, 1813, at the age of 66. He had suffered a paralytic stroke in November of 1812. Although he showed some improvement in the next few months, he remained bedridden. In February 1813 he suffered another stroke that left him unable to speak. He passed away soon thereafter.

In the Chancellor’s day, his affliction would have been known as apoplexy. First identified by Hippocrates himself more than two thousand years ago the name translates roughly to struck down by violence or to be struck down utterly.

Like almost every other disease and affliction in humans it was thought to be caused by an imbalance of the four humours; blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. The idea that four humours were responsible for the health or lack thereof, of a person was a belief that went back thousands of years into history. So far in fact that the actual origins of the idea are lost to history. The cause of the imbalance was attributed to many possible factors. These ranged from divine justice to a disposition of the person’s body type to intemperance and immoderation. Some even thought that “straining at the stool” could bring on apoplexy. It was only in 1812 that a young French doctor by the name of Jean-Andre Rochoux firmly stated that apoplexy was a hemorrhage of the brain. This idea had been around for many years, but Rochoux was the first one to make the statement firmly and two years later he published a monograph on the topic.

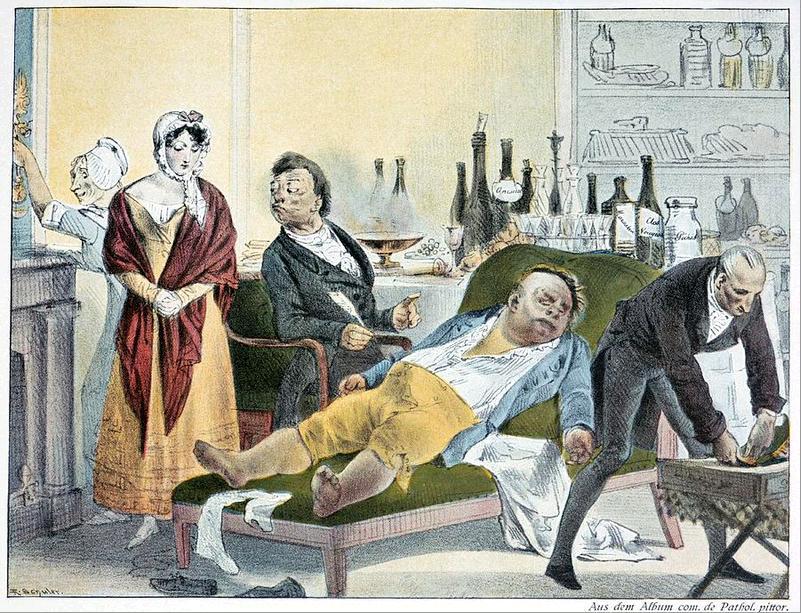

As far as treatment went there was little a doctor could do except to bleed the patient in an attempt to rebalance the humours. In some cases where the apoplexy was thought to be brought on by large indigestible meals the doctor might add induced vomiting and enemas to the treatment regimen. It is unclear what the Chancellor’s physician, most likely William Wilson, did to treat the Chancellor.

Patients who suffered an apoplexy rarely ever recovered, which makes the signs of the Chancellor’s recovery after his first stroke all the more remarkable. Patients rarely recovered full control of their bodies, and some suffered with other neurological issues. The loss of the ability to speak, such as what happened to the Chancellor after his second stroke, was very common. There was no cure for an apoplexy and very few people lived very long after suffering one.

UPDATE: With some more digging some of the treatments that Chancellor Livingston’s physiciain Dr. William Wilson used have come to light. On December 8, 1812 Dr. Wilson consulted with Dr. Romeyne and Dr. Stearns. There were doctors of those names practicing in Albany at the time so its possible those were the men consulted. On December 31, 1812 Wilson dressed something on the Chancellor, bled his and gave him a physic of Malaci, mustard seed and isinglass. Malaci remains unidentified to this point but mustard seed was thought to draw out toxins and warm the blood and muscles, on the other hand prolonged exposure can lead to first degree burns. The isinglass was essentially a jello made from the swim bladder of sturgeon or cod.

On January 31, February 13 and February 18 Dr. Wilson returned to change dressings on his patient. On February 24 he consulted with a Dr. Bard about the Chancellor’s condition. On February 25 Wilson noted that Mr. L. died Thurs evening 6 o’clock.

Leave a comment