On May 17, 1776, Chancellor Robert R. Livingston wrote to his friend John Jay. Livingston had been searching for lodging for the two of them and their wives close to Philadelphia but outside the city proper. They were both planning to return to the Continental Congress after extended absences. Livingston wrote

“However I have provided three bedrooms & a large parlour in a retired country house about two miles from Bristol upon the banks of the Shamony (now known as the Nashaminy Creek) where we shall have plentiful provision for our horses, good fishing before the door, a tavern about ¼ of a mile from us to lodge our friends & in short every thing that we can wish to render our situation agreeable.”

As good as this situation sounded it was not to be as John Jay’s wife became ill and he chose to stay with her rather than return to Congress at that point. But if they had taken these lodgings outside of Bristol what would the “good fishing before the door” have looked like?

First, their fishing poles. Their poles could have been anywhere from 6 feet long up to 18 feet long. They would have been made of hazel or some other flexible wood. Some were even made of imported bamboo. Some poles had guide holes put on during the late 18th century, but these holes were notoriously unreliable and often broke off the pole when a fish was on the line.

Livingston and Jay would have had a few choices for line. The simplest would have been a linen line, essentially string. Another option was braided horsehair line. This line was always made from the tail hairs of a horse and never the mane as the hair from the mane was too brittle to stand up to any pressure from a fish and the line would break. Horsehair line is still used today and is known as tenkara line. Just coming into use as fishing line in the late 18th century was silkworm gut. Despite having advantages as far as strength, flexibility and being nearly clear, the gut was slow to be adopted mainly out of adherence to tradition among fishermen. Most of the time the fishing line was attached to the tip of the fishing rod using a whip knot.

On the other end of the line was a hook. The hook was generally made of steel and made by a blacksmith. Unlike modern hooks, 18th century hooks did not have an eye and were usually attached to the line using a whip knot.

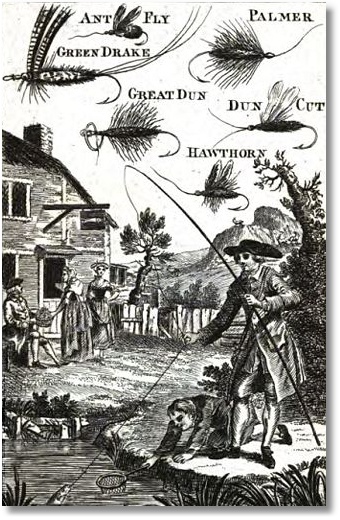

There were two main types of recreational fishing in the 18th century, bait fishing and fly fishing. Bait fishing used some type of bait, as one might expect. This could be anything from worms and minnows to cheese or bread. The bait was hung on the hook and weighted down with lead weights so it would not float. A piece of cork strung above the hook would float on the water and sink when a fish took the hook. Fly fishing, on the other hand, used a hook tied with thread and feathers to look like an insect as bait. Books were published on how to make the best-looking flies. One of the major differences between 18th century fly fishing and modern fly fishing is the casting. With a long pole, an 18th century fly fisherman would dangle the fly over the stream so that the bait just touched the water as opposed to today’s fly fisherman who go through an elaborate routine of casting and letting some of the line rest on the water. Despite having been around for hundreds of years by the end of the 18th century fly fishing was not the dominate style of fishing, that honor belonged to bait fishing. However, by 1830 fly fishing boomed in both America and Europe.

As said earlier, Livingston and Jay were unable to take up residence in the rooms that had such good fishing nearby because Jay chose not to return to Congress at that time. What Livingston’s letter does tell us though is that both he and Jay were sportsmen who enjoyed wetting a line now and then.

Leave a comment