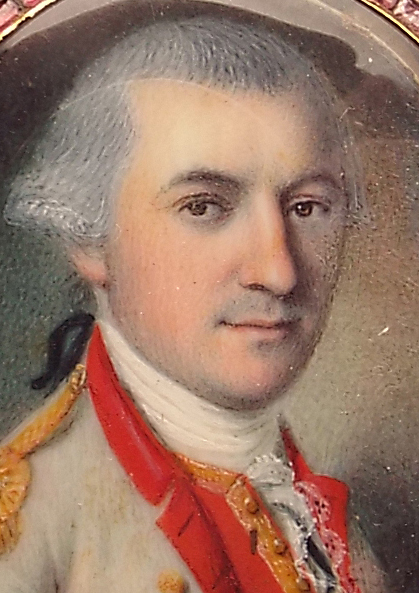

On December 19, 1777, somewhere between 11,000 and 12,000 men of the Continental Army and 400 women and children camp followers marched onto the plateau of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania to settle into their winter quarters. They were not the beaten, dispirited, and starving soldiers of myth but instead the soldiers of George Washington’s army were proud of their performance against General William Howe’s British regulars in recent months. Though they had been pushed back at each of the major engagements of the Philadelphia Campaign the British had paid for every step they took on their way to Philadelphia. They were joined by soldiers of the Northern Army, like Henry Beekman Livingston’s 4th New York Regiment who had, just two months before, delivered a beating to General John Burgoyne so bad that he had surrendered his whole army to the Americans.

Interestingly the most pervasive myth about Valley Forge is how brutal a winter it was. The winter of 1777-1778 was not the worst winter the army would face in terms of cold. The winter was challenging though in that bouts of freezing temperatures were as common as bouts of temperatures above freezing. Snow and rain occurred frequently. All of this led to camp roads and paths either consisting of sucking mud or ankle breaking frozen ruts.

With winter setting in the most desperate immediate need of the army was clothing and shelter. With no clothing readily available the soldiers set about building 14’ x 16’ log huts to live in for the winter. Each hut contained a fireplace and were considered relatively comfortable considering the alternatives. Soon 2,000 of the huts spread along the plateau in neat rows. This number only grew as another 8,000 men joined Washington’s army over the winter and spring. Soldiers also constructed trenches and other defenses should the British decide to march out of Philadelphia to attack the camp.[i] The camp looked and operated like a miniature city.

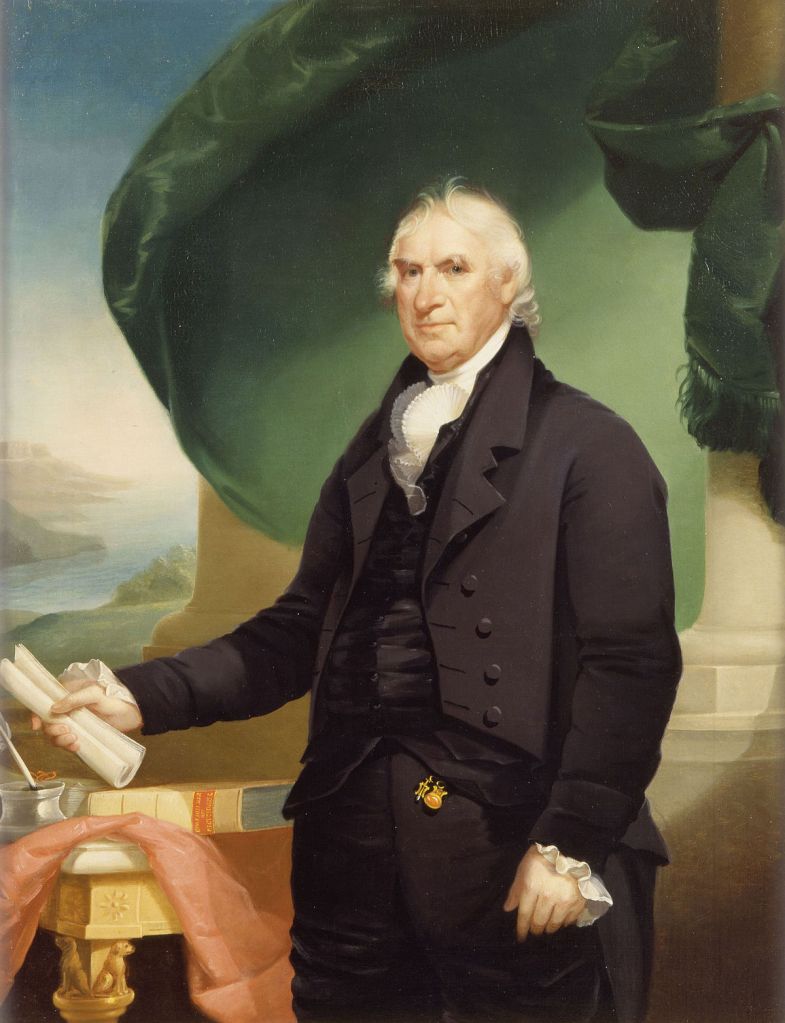

Clothing the army was the responsibility of the individual states. On December 25, 1777, Henry Beekman Livingston wrote to Governor George Clinton of New York that “wholly destitute of clothing the men and officers are now perishing in the field.”[ii] He feared the dissolution of his regiment if the supply issues were not addressed. He had marched into Valley Forge with only 287 men of which only 171 were fit for duty[iii] Henry’s pleas were soon joined by those of Washington himself who wrote to Clinton and the New York State government on December 29, 1777, that they needed to put their “most serious and constant attention” to clothing their troops.[iv] Soldiers and camp followers had to get creative in how they clothed themselves. In the case of Henry Beekman Livingston’s enslaved servant, Jack, he turned his blanket into a set of clothes which of course helped to cover his nakedness but meant he endured the winter nights without a blanket.

Food was not in short supply early in the encampment. The National Park Service estimates that each soldier was receiving a ration of ½ pound of beef a day in January.[v] Not all of the food shipped to the camp was good though. On December 20 a committee sent to inspect food delivered to General Ebenezer Learned’s brigade found the beef to be “not fit for the use of human beings.”[vi]

By February the food situation in the camp had deteriorated. Washington wrote to Clinton of New York that describing what he called “a famine in the camp.”[vii] On February 12, 1778 Washington ordered General Nathanael Greene to conduct a Grand Forage both to stop the British from collecting supplies and to gather supplies for the army.[viii] At least 1,500 soldiers from Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and New Jersey took part in the forage which covered parts of all of those states. The forage lasted six weeks but was ultimately a success.[ix]

In the meantime, members of the Oneida tribe who had served with the Continental Army since at least mid-1777 let their people know how bad the situation in camp had grown. Soon more members of the tribe were on their way to Valley Forge with 600 baskets of white corn. When they arrived, an Oneida woman named Polly Cooper showed the troops how to make the corn edible. She stayed at Valley Forge serving as a cook and nurse.[x]

Of course, nurses and doctors were in demand as disease ran through the camp. Despite sanitary precautions being taken and a robust smallpox inoculation program being instituted disease was almost inevitable. By the time the army broke camp in June 1778 more than 2,000 men had died of influenza, typhus, typhoid, and dysentery.[xi] Henry Beekman Livingston sickened to the point he had to be removed from the camp, but he recovered from his illness.

With the spring came supplies of uniforms and food from the states. The soldiers regained their strength and their pride. Under the tutelage of the Baron von Steuben they learned how to become real soldiers able to stand up to the British army in an open field battle.

[i] https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/valley-forge-history-and-significance.htm

[ii] Henry Beekman Livingston to George Clinton, December 25, 1777, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York 1900

[iii] https://valleyforgemusterroll.org/4th-new-york-regiment/

[iv] “Circular to the States, 29 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0037. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 13, 26 December 1777 – 28 February 1778, ed. Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003, pp. 36–39.]

[v] https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/valley-forge-history-and-significance.htm

[vi] “From a Committee to Inspect Beef, 20 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0588. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 648–649.]

[vii] “From George Washington to George Clinton, 16 February 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0466. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 13, 26 December 1777 – 28 February 1778, ed. Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003, pp. 552–554.]

[viii] “From George Washington to Major General Nathanael Greene, 12 February 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0430. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 13, 26 December 1777 – 28 February 1778, ed. Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003, pp. 514–517.]

[ix] Herrera, Ricardo A. Feeding Washington’s Army: Surviving the Valley Forge Winter of 1778 The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2022

[x] https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/oneida/

[xi] https://www.nps.gov/vafo/learn/historyculture/valley-forge-history-and-significance.htm

Leave a comment